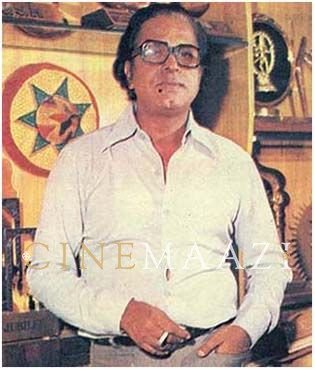

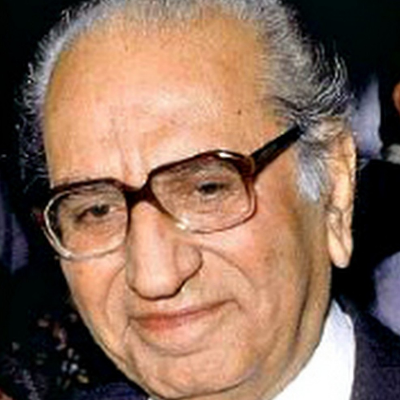

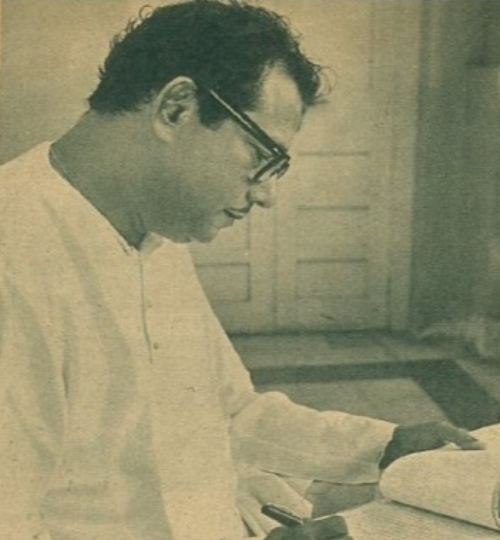

Amitabh Bachchan once said of him, ‘[He] used to make films from the heart. And only from the heart…’ Dulal Guha directed some of the biggest hits of the 1970s, like Dushman, Do Anjaane and Pratigya. Anirudha Bhattacharjee met up with his son, Putul Guha (Partha Guha), in December 2019 in Mumbai, to talk about the illustrious career of Dulal Guha, which lasted thirty-five years, from 1955 to 1990.

‘A refugee Bengali teenager from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) came to India in search of a better life. He married a wonderful lady and the couple had four amazing children. That boy went on to become a successful contributor to the Indian film industry and society. His four children had spouses from four different regions: Gujarat, Bengal, south India and a Punjabi (Sikh) migrant from Iran. Their children have chosen partners from other communities as well. A Maharashtrian, a Belgian, a Catholic and a Muslim. In spite of being such a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic family, religion, caste, language, etc, has never been a divider. That refugee had learnt to embrace pluralism and brought up his children to respect all religions, caste, and languages. I am sure our family is a perfect example of national integration solely because of his ideals. Imagine … if they did not let that refugee boy into this country, I would not have this wonderful family.’—Tanushka Alva, Tasmania, Australia

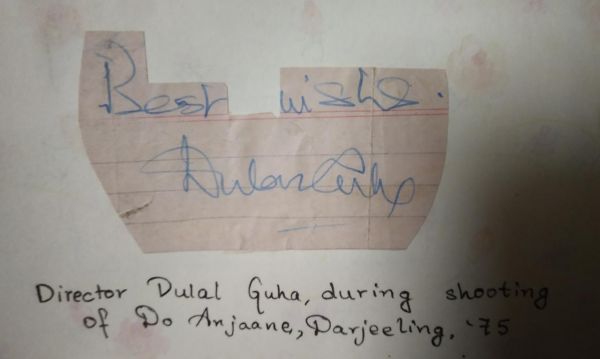

‘Legendary lyricist Anand Bakshi was once travelling to a shoot in Nashik or Shirdi. A truck kept blocking his attempts to speed on the highway. Even as he tried to overtake the truck, his eyes focussed on something written on the rear of the truck. After reaching the location, he called my father and announced, “Bhaiya, got the beginning of the song,”’ says Putul Guha in a discussion with the author.

The lines Bakshi wrote next were:

Sachchai chhup nahi sakti banawat ke asulon se

Ke khushboo aa nahi sakti kabhi kaagaz ke phoolon se

Anand Bakshi had the habit of putting to tune some of his lyrics. He may well have sung the part to Dulal Guha.

Putul Guha continues, ‘Baba came to us and hummed the song, mentioning that it would be a super hit. You see, that was the genius of the people then. A super-hit song was envisaged from the unlikeliest of places, put to tune, recorded and filmed – all in a matter of days. Baba had in his mind ticked the boxes which fit public expectations. A truck driver, rustic, alcoholic, dancing to a song which had its origins in a pithy comment at the back of a truck. And Rajesh Khanna. The small towner would lap it up. It remains widely popular fifty years later…’

Early Days

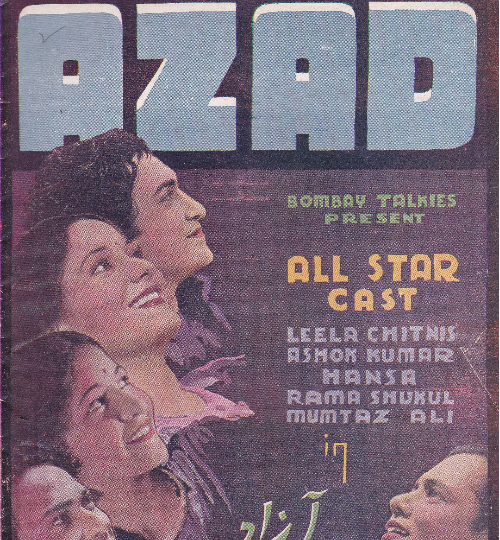

Dulal Guha was born in Barisal on 2 April 1929. He was affectionately called Monu by his parents. His father Rohinilal Guha was a police officer. A diabetic, it was severe gangrene which led to his death when he was around 26-27 years old. His mother Nirmala Guha was from Swarupkathi (now Nesarabad), a village near Barisal. After her husband’s death, Mrs Guha was left on her own; and the only possible avenue she had was to go back to her mother’s place. Her maternal family were Roychoudhurys, probably zamindars at some point in time. Young Dulal did his schooling at Beni Madhab School. He loved painting, and after partition, when he moved to Calcutta for work, he started painting film posters.

PG: Ek Gaon ki Kahani (EGKK) was the film Bose had in mind right after Bandish. But Bandish was sent to the Berlin Film Festival in the non-competitive section, and Bose had to be there. The dates for EGKK was already given to the actors. Shree Sound Studio had been booked, technicians had their schedule earmarked, etc. Hence, Bose had to delegate all his work to Baba. Jagdish Mukherjee was Satyen Bose’s chief assistant, but Bose advised him to support Baba for EGKK.

Talat Mahmood played the lead role in EGKK. Talat’s singing skills probably worked in his favour, as the film had some excellent songs. Mala Sinha, Abhi Bhattacharya and Nirupa Roy had also been signed up for the film.

Few people know that Bhanu Banerjee, arguably the most famous comic actor Bengal ever had, was among Guha’s best friends. They had met in Calcutta. Guha had promised Bhanu during the making of Bandish – in which Bhanu essayed the role he had in the original Bengali film Chhele Kaar (1954) – ‘If I make a film, you’ll be there.’ Bhanu had a cameo in EGKK. By that time, Bhanu was very busy in Calcutta, shooting almost all through the month. But he came down to Bombay specially to honour the friendship.

At this point in time, Bengali stories and films were a favourite with film-makers in Bombay. Like Bandish, EGKK too was based on a Bengali film, Sahar Theke Durey (1943), by novelist and film-maker Sailajananda Mukherjee. Bose meticulously avoided following the original when it came to shot-taking and stylization. While the original was definitely more aesthetic, EGKK with a plethora of songs and typical Hindi film melodrama was more commercial in its approach, a template followed by Tarun Majumdar when he remade Sahar Theke Durey which was censored in 1979 but had a delayed release in 1981.

EGKK was a moderate hit, following which Guha signed three films in succession: Patwaar, Rahi Badal Gaye and Ek Akeli. One of the producers was actor Lalitha Sinha’s husband, who also managed Shree Sound Studio. The stars signed up included Abhi Bhattacharya, Nimmi, Mala Sinha and Bharat Bhushan. None of these films progressed beyond a few reels. His only daughter Ankana (Fultu) was born during this period, in June 1958.

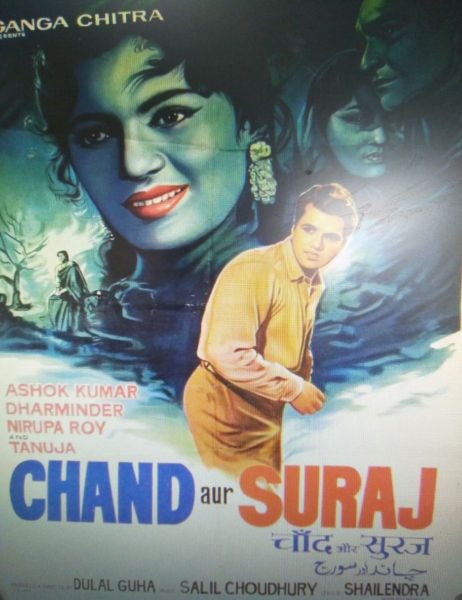

Despite critics not quite going gaga over the film, it was doing rather well, when the India-Pakistan war was formally declared. This led to blackouts in the evening, and only noon and matinee shows were allowed. After thirteen weeks, the film had to be withdrawn from Krishna theatre (renamed Dreamland) at Grant Road, Bombay. Today, despite an interesting storyline, some nice tracking, panning and mid-shots coupled with excellent music, the only enduring image remains Tanuja’s swimsuit act in the dazzling composition ‘Bagh mein kali khili’. And interestingly, the censors had no objection to the rather bold outfit for its time. One might find it interesting that ‘Kisine jadoo kiya’, admirably rendered by Mukesh, was actually shot for the film, but not used as ‘Bagh mein kali khili’ seemed to be a better alternative for the box office.

The Rise

Chand aur Suraj might have not done well commercially, but it had producers flocking to Guha’s place in Sion where he had moved after EGKK. One of them was R.C. Kumar, who had bought the rights to a story titled Bin Maange Moti. After going through the script in detail, Guha backed out as he realized that the story was a blend of Dil Ek Mandir (1963) and Phool aur Patthar (1966). The film, with Dharmendra and Meena Kumari in the lead, had to be shelved. As Guha had been given a signing amount, he helped Kumar with the story of Izzat (1968) which was directed by T. Prakash Rao. Guha was in the habit of writing stories, and had written for the very popular AIR show Hawa Mahal as well.

Three films followed in quick succession: Jyoti,(1969) produced by Alexander Devdas, Dharti Kahe Pukar Ke (DKPK) by Dharmendra’s secretary Dinanath Shastri, and Yusuf Teendarwajawala’s Mere Humsafar (1970).

Shailendra, who was supposed to write the lyrics, as he had done in Chand aur Suraj, passed away before the song sessions could start. This film was dedicated to him.

It is interesting to note that the characters in DKPK were villagers living around Calcutta. Part of the intent to set up a contrast between the soul of a village and the intellect of a city, very much part of the era’s Nehruvian socialist model. Guha was a small-town man himself.

The only thing that worked in Jyoti was the music.

PG: The producer A. Devdas was probably an important member of the Football Association in Bombay. He used to do our bookings at the Cooperage Stadium. S.D. Burman, as you know, was always there for important matches. Baba was very fond of S.D. Burman and requested him to write the music for Jyoti, something he consented to after hearing the story. I remember SD calling at 5 a.m one day. We had two phones then, and he had called at the hall number. I picked up the phone, and there was this sweet but stentorian voice: 'Dulal aachhe (Is Dulal there)?’ I asked for the caller’s name, and I can never forget the voice at the other end: ‘Aami Sachin Dev Burman bolchhi (This is Sachin Dev Burman speaking).’ I hurriedly called my father who immediately set out for SD’s house at Linking Road. He returned a few hours later with the news that SD had created a cracker of a tune.

The song: ‘Soch ke yeh gagan jhoome’. Few will argue that this is the most ethereal Lata Mangeshkar–Manna Dey duet ever.

The Seventies

The failure of Jyoti and Mere Humsafar meant that producers like R.C. Kumar and Malik Chand Kochar, who had expressed interest in working with Guha before, abandoned him. It was perhaps the sudden change in attitude of people around him which led Guha, in a self-deprecating tone, to tell the press, ‘No producer has ever repeated me.’

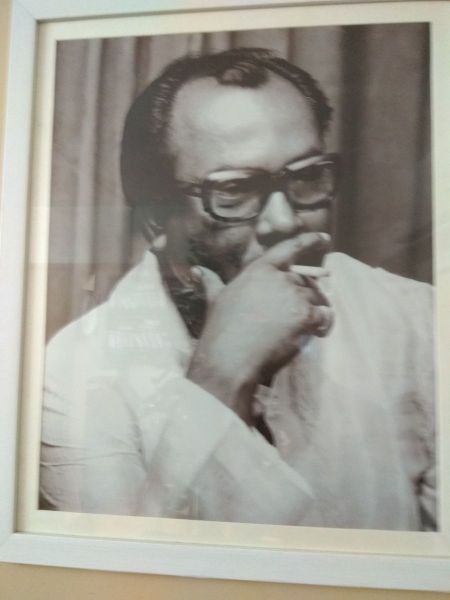

%20with%20Ratan%20Bhattacharya-Courtesy%20Abir%20Bhattacharya.jpg/5_During%20Zanjeer%20(Dushman)%20with%20Ratan%20Bhattacharya-Courtesy%20Abir%20Bhattacharya__429x600.jpg)

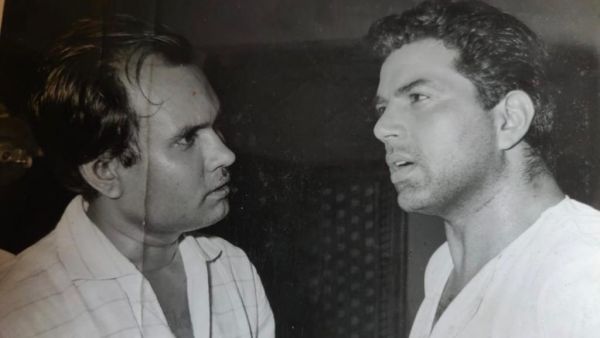

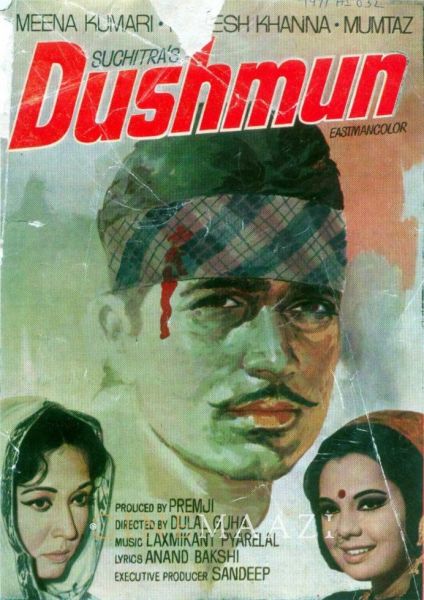

Around that time, the reigning king was Rajesh Khanna. He and Mumtaz were signed, and the shoot started in 1970. One of the reasons Guha wanted to use the truck was to add some dynamism to a film which had an emotional core. The journey of a truck helped in showing more locations, characters, cultural differences, etc. Contrary to horrendous stories about Rajesh Khanna’s star tantrums, he created little hassle. Also, a rapport had developed with the team, as he was loving the character.

PG: My father had a good working relationship with Meena Kumari as he had worked with her in Bandish. Some sittings had also happened during Jyoti. While the discussion about casting was on with Premji, Baba wanted to have Meena Kumari for the role of the elderly character and went to meet her with the offer. She was extremely sick at that time. Her body used to shiver. She had to sit near the sigri. In spite of difficulties, both physical and mental, she gave her best. She did not even take a body double, except for long shots and running scenes.

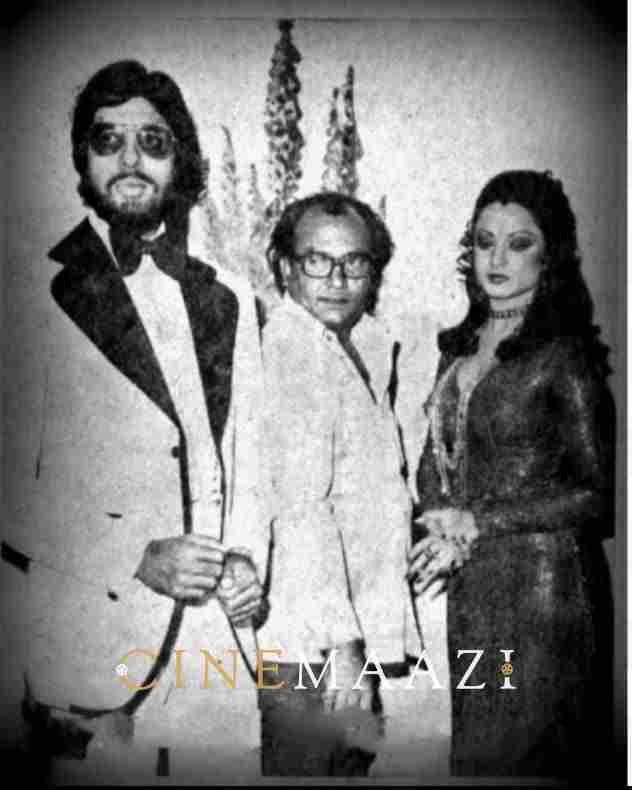

Released on 7 January 1972, at Ganga, Jamuna and other halls in Bombay, Dushman, was a roaring success and remains one of Rajesh Khanna’s most celebrated films.

Guha named his next film Dost.

PG: Baba wanted to use the simile of a tree in the song ‘Gadi bula rahi hai’. A tree which serves humanity without asking for anything in return. And the lyrics were written to convey that, with the train thrown in as a motif. Premji had a place near the railway tracks at Dahisar, a suburb near Bombay. I do not know, but there could be some influence of Ray’s Apur Sansar (1959) here as you suggest. Though Baba made films which were completely commercial – as this was the mantra you needed to survive in Bombay – he was a technically competent man. Hindi was not his strong point, hence he had to rely on writers – B.R. Ishara, Shafiq Ansari, among others. He rarely did storyboards except for some shot divisions; storyboards have never been in fashion in Bombay. But he used to direct everything himself. Though Desh Mukherjee, an exceptional art director worked with him most, Baba would call the shots and ask for exactly what he wanted in terms of colour, décor, etc. He used to operate the camera himself in most cases, even when he was using the Mitchell model which allowed him little flexibility as it was heavy and needed three to four people to lift. Lenses had to be changed manually every time. In the 1970s, he shifted to a particular model of Arri which was lighter. One could zoom using normal lenses as well. This helped him to zoom to close-ups, for example, in Do Anjaane (1976).

We had shifted to Pali Hill from Sion around 1972–73. Jeetu was our neighbour. A wall separated our buildings. He never used to enter our apartment through the main gate, preferring to jump over the separator, spend some time playing cricket with us boys, and then go up to meet Baba.

There is an interesting story regarding the casting of Dost. The actor who was in Guha’s mind when he wrote the character of Gopi was Sanjeev Kumar. One fine morning, a tall and enthusiastic young man met Guha. He had with him a couple of letters which were written by Guha to him as replies to his fan mail (Guha’s secretary Raman would respond to the fan mail and Guha would sign). The young man had graduated from the FTII and had done a few films. He was Shatrughan Sinha. Sinha got the role, and incidentally, became a very good friend of Sanjeev Kumar too, whom he replaced in Dost.

Dost was released on 12 April 1974, at theatres like Jamuna and New Empire. The feedback given by Dharmendra’s family members who were there at the premier two days back was by no means positive. They felt that it was another Satyakam (1969) – high on class, but not targeted at the masses. Satyakam was Dharam’s first home production. Punchhe, his younger sister’s husband, had lost around Rs 3-4 lakhs on the film. Dharam, who flew to Srinagar on 11 April for a shoot, was visibly perturbed, as he had invested a lot of time and energy in Dost.

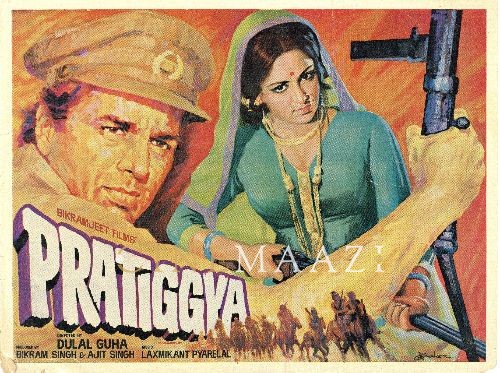

This was followed by a heavy breakfast at our house. Baba phoned Premji to come down. In the meantime, Dharam-ji had also called home, and his brother Ajit came down with a packet of sweets, a flower bouquet, and a suitcase which had Rs 50,000. That is how Pratiggya kicked off.

PG: After Dost, Shatru wanted to make a film with Baba produced by his secretary Pawan Kumar and his cousin Yogi. Titled Khan Dost, the script was by the Ghai–Bhalla [Subhash Ghai and B.B. Bhalla] combo. After hearing the outline, Baba insisted on Raj Kapoor for the role of the jailer. Baba was a huge fan of Raj Kapoor and it was like a family ritual to see his films at the theatre. Friday first show. The problem is that Baba was so much in awe of Raj Kapoor that Raj-ji was all over the film. When the film released, Pawan Kumar and Yogi were sitting in the house and discussing the reports and the audience reaction. Both insisted that the opening shows were houseful. I had to intervene and set the record straight as I was there at the show. The show was certainly not houseful. Pin-drop silence followed. Suggestions for improvement started coming from all quarters. Subhash Ghai said, no, my story cannot be bad. Following a joint decision, Ghai, a director himself, tried to salvage the film. It did not help.

Irrespective of the differences which cropped up during that time, both Ghai and Shatru remained good friends of Guha. Shatru worked with Guha again in Sagar Sangam (1988).

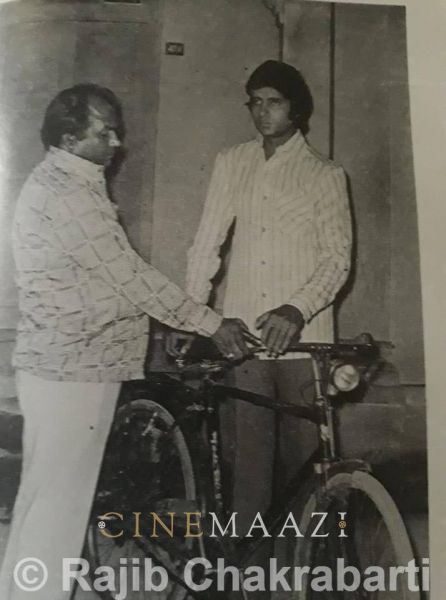

Around the time Khan Dost was in the making, a first-time producer had come down from Calcutta. Kushaljit Singh Juneja aka Tito, a film distributor, wanted to produce a film. The only criterion was that it should have Amitabh Bachchan.

After the pleasantries were exchanged and commercials discussed, the task was to find a story dramatic enough to attract Amitabh. And it was Putul’s grandma’s (Nana Ma) suggestion that worked.

Do Anjaane used many important landmarks of the city as backdrops, among which the Great Banyan tree at the Botanical Gardens was one. One of most loved songs featured on Amitabh, ‘Luk chhip luk chhip jao na’, was shot there. It proved difficult to get the kid run to the exact spot for the shot, and this was negotiated to the satisfaction of Guha after multiple attempts with the kid’s mother standing at the spot with a biscuit in her hand, inviting the toddler.

Kabir Bedi had to be replaced by Prem Chopra after the first shoot near the swimming pool at the Grand. Arati Das aka Miss Shefali, Bengal’s most famous cabaret dancer, played herself in the film – at the Princes’, the nightclub at the Grand where she was employed. And then there was Mithun Chakraborty. Do Anjaane was his first release, though he had acted in Papi Devta, a film produced by Madan Mohla. It was among the many films of Dulal Guha which could not be completed.

People who grew up during the 1970s might recall there were debates on the ending of Do Anjaane. Guha had clarified to the press that he had to shoot two separate endings as the producer and the distributors wanted a happy ending. By the time the second premier show was held on 3 December 1976, Guha was in Tirupati, after which he was travelling to Madras for discussions on Dil ka Heera (1979). Gulshan Rai, the distributor for Bombay, against the wishes of Guha, had used the happy ending.

PG: The original ending was as per the story, where the couple separate at Bagdogra airport. The screenplay by Nabendu Ghosh had Rekha leaving the airport on her car with the refrain ‘Koi mere saath chale na chale’ being played in the background. That had to be changed for a more commercially viable alternative. Do Anjaane was actually a film for multiplexes, and not for the front-benchers. If made today, it would have done much better, though it did good business even then.

The Evening

The critical success of Do Anjaane – most periodicals barring a few like Filmfare gave it a good review, including the otherwise difficult to please Bengali literary periodical Desh – threw up possibilities of a few more films with Amitabh. One was planned during the time Dhuan was made. The story, named Devdoot, written by Kamleshwar was about a street urchin who indulges in child trafficking – but with an intent to help destitute children and rich childless couples. The film never got made.

The year after Do Anjaane, Baba was involved in buying a farmhouse in Nashik. And getting it in shape. His travels to Nashik had become very frequent. For story sessions, he used to invite producers and associated people to his farmhouse. The fascination for Nashik started when he was shooting DKPK and, later, Dushman. Most of the outdoor shoot was done in Nashik. He was such an expert on Nashik that producers/directors who wanted to shoot in Nashik would come to him for consultation. Also, he was not exactly a religious man, but he loved to go to Shirdi, which was near Nashik. Producers then started complaining that Guha was not focussing on his work. True. He had lost interest. Though he directed five films after Do Anjaane, his general reaction to film-making was: is the script ready? Ok, let’s shoot.

Guha suffered multiple organ failure on 2 January 2001, at his farmhouse. He had not gone to Bombay for over two years at that point in time. The doctors at Nashik advised the children to take their father to Bombay for better treatment, something which they could do only with extreme difficulty. He went from Nashik on the condition that he would return. His wish remained unfulfilled. He returned to his Versova bungalow from Leelavati hospital, on January 25, only to be readmitted the next day. Guha passed away on 14 February. He was seventy-two.

Epilogue

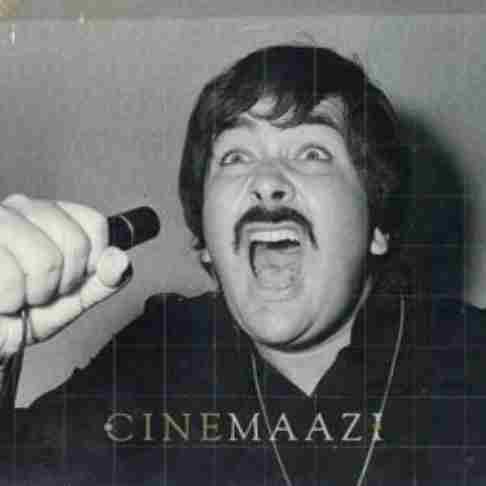

PG: Many years ago, there was a young boy in Calcutta called Kedar Bhattacharya, who played the tabla in his father's Jatra group. One day, the singer meant to perform was late. In order to placate the restless audience, the organizers suggested the young tabla player sing until the vocalist arrived. The boy took the microphone, and as fate would have it, 'Sachchai chhup nahi sakti' was the song he performed. The boy never played the tabla again but went on to be a famous singer.

Years later, this boy - now known as Kumar Sanu - acted in a Bengali film called Gaane Bhuban Bhoriye Debo, which I directed. "What are the chances," Sanu told me during the shoot, "that years after I made my debut on stage with a song from a filmmaker's movie, I would be producing, and acting, in a film directed by his son?" What he was trying to convey, I reckon, is that life always finds a way to come full circle...

Interviews conducted

Putul Guha, son of Dulal Guha. Without him the feature could not have been written

Tanushka Alva, granddaughter of Dulal Guha, daughter of Ankana Guha Alva. She is based in Tasmania.

Acknowledgements

Rupali Guha, daughter-in-law of Dulal Guha (Married to Pintu Guha)

Kaustubh C. Pingle, Dubai-based film researcher

Abir Bhattacharya, film researcher, Calcutta

Rajib Chakrabarti, Calcutta-based film lover

Balaji Vittal, Hyderabad-based film researcher

Debasish Basu, Calcutta-based engineer who was there in the crowd at Botanical Gardens when ‘Luk chhip’ was shot

Rajesh K Singh, Jaipur based film researcher

S M M Ausaja, Bombay based archivist

Tags

About the Author

Anirudha Bhattacharjee is an alumnus of IIT Kharagpur who works as an SAP consultant. He divides his time between work, family, singing, solving puzzles, quizzing, and watching football or films of Wilder, Hitchcock, Satyajit Ray and anything that has the semblance of a biopic/comedy/noir/alternative history. A writer by accident, his area of interest is mainly Hindi and Bengali cinema between 1950 and 1985. He is the co-author of the National award-winning book R.D. Burman: The Man, The Music, the MAMI winner Gaata Rahe Mera Dil and the critically acclaimed S.D. Burman: The Prince-Musician. Anirudha stays in Bangalore with his wife Sudipta and sons Aritra and Shaunak, all of whom share his passion for cinema.

.jpg)