The Accidental Archive: How Radio Listeners Became the First Custodians of Early Indian Cinema

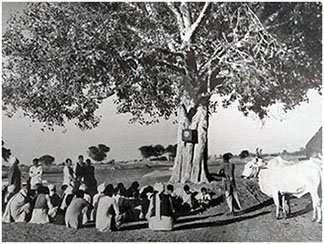

For a large part of India in the early and mid-twentieth century, cinema did not arrive as an image. It arrived as an aural experience. Back then, theatres were concentrated in cities and tickets were expensive. Cinema was not easily accessible for the majority of Indians. Film prints rarely reached small towns. But with single crackling speakers, radio seeped into villages, small towns, and homes where cinema was a distant luxury. Radio sets became the primary connector between films and their listeners. This way, for many, cinema did not come through the eye but through the ear, and radio made films travel where the projector could not.

This created an interesting trio: radio, cinema, and its listeners. For them, film did not flow from reels but from radio sets. Programmes travelled invisibly through the air, crossing distances without tickets, transport, or literacy, turning living rooms into makeshift cinemas.

Here’s what changed because of that difference. Film music, which might otherwise have remained confined to cinema halls or to the homes of those who could afford records, slipped beyond those limits. Songs moved out of elite drawing rooms and into bazaars, courtyards, tea stalls, and village squares. One broadcast could gather an entire neighbourhood around a single receiver. A melody heard once in a theatre now entered daily life.

Listeners, through shared experience, also became India’s first true nationwide cinema network, who were not just consuming film music but making it part of their lived experience. And in that act of listening, discussing, and remembering, they accidentally did the work of archivists long before formal documentation and preservation happened.

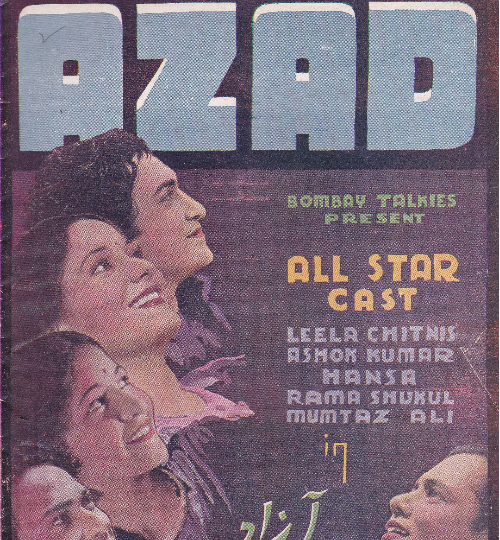

This mattered because film archiving in India was virtually non-existent at the time. By the time the NFAI came into being in 1964, most early cinema had already been lost. Cinema in its early decades was treated as disposable entertainment, and studios saw little value in preservation. A majority of prints of films made before 1950 no longer exist. Out of the vast output, only fragments remain. Some of the most historically significant works are gone forever, surviving only in stills, reviews, songs, publicity materials, and recollections. And yet, the cinema of that period did not disappear.

This happened because a radio listener in Kanpur who wrote down songs from a popular film created a record no studio ledger preserved; a teenager in Kolkata who memorised the voice of a singer became a living repository; a woman in Pune who saved a magazine mention of a radio broadcast date provided a timestamp that no archive captured; and in towns like Jhumri Telaiya, archiving did not require vaults or catalogues but love for cinema.

It’s interesting to note that listeners remember cinema differently. They recalled a singer’s inflection, a composer’s signature tune, and a lyricist’s turn of language. These were details visual records alone could not capture. Today, when a researcher tries to identify uncredited artists or undocumented films, it is often oral memory, reinforced by listening habits, that provides clues.

Rethinking the Archive

A Call to Listen Again

On World Radio Day, it is worth recognising the listeners who unknowingly built one of Indian cinema’s earliest archives. Their practices remind us that cultural memory depends on participation as much as protection. Before vaults, there were drawing rooms. Before archivists, there were fans. Before preservation policies, there was listening. Indian cinema survived not because it was formally secured, but because it was cherished — and love, unlike nitrate, does not decompose.

About the Author

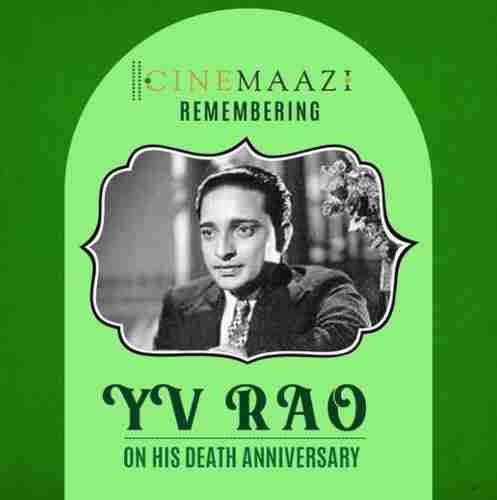

Asha Batra is a film historian, archivist and exhibitor. The Founder Trustee of Indian Cinema Heritage Foundation, Asha also heads Cinemaazi Research Centre, the Foundation’s flagship project which is creating a research based digital encyclopaedic resource of Indian films and its people.

.jpg)