"Gwalan" Proves A Thrilling Entertainment !

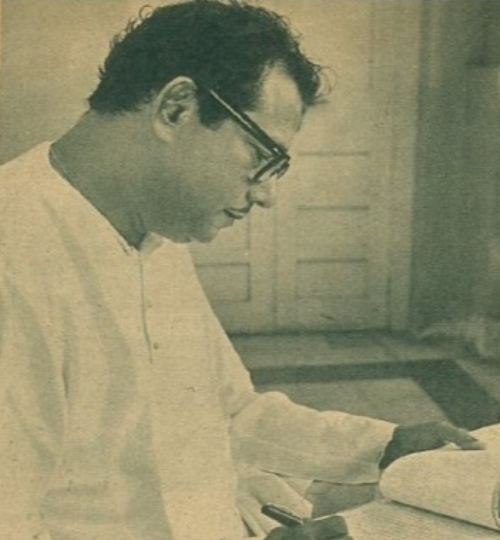

This picture is written, produced and directed by Baburao Patel, India's foremost critic and the father of film criticism in this country. The very name Gwalan (1948) suggests that the great critic had decided to give us mere entertainment and nothing more and he says in his booklet of the picture: No one is asking you to believe in this story. In fact, the only truthful thing about it is that it never, happened. But it is there to entertain and make the people forget a few worries, for a while at least." After this characteristic candour, there can't be quite so sore because Patel did not use his opportunity to give us a purely progressive picture, which almost all critics in the country expected from the editor of the most popular and dangerous film magazine.

Why they expect this, no one can say.

It may be because in his forceful writings Baburao himself insists on motion pictures having more purpose than mere entertainment. It is, therefore, natural that others put the great critic to the touchstone of his own criticisms.

BLIND JEALOUSY

Before proceeding to the artistic and dramatic contents of Gwalan, many of us-the press gallery of hungry vultures in this case-had a rude surprise at the credit title: "Dialogue by Baburao Patel." We asked one another:

"When did Baburao Patel start writing Hindustani?" Someone remarked, "Oh, he will someday write even the Zulu language if it pays him". That was no doubt an unkind remark prompted by persona I jealousy. For, all the journalists in the country, counting the present scribe are more or Jess jealous of Baburao Patel's forceful pen and success as a critic. But personal jealousy should not blind us to the unique talent of the man as journalist, critic, artist and businessman.

What Baburao Patel stands for today is the result of deep and devoted study of 25 years. His choice and extensive library should prove that the man has spent hours and years in different studies. The very pride of the man compels him to approach every new subject with scholastic perseverance so that he may not have to blush before others. In fact, personal pride characterises almost all the writings and behavi¬our of Baburao Patel and though he has been ruthlessly, and al¬most always unfairly, criticised by his jealous professional brothers, his pride, born out of personal achievement, has saved him from being hurt. That probably explains his lofty contempt towards little fellows who never rise above themselves and never see good even in good things just because they are done by Baburao Patel. The press criticism of "Draupadi", Baburao's previous picture, proved this and all the little minds disagreed in a chorus of jealousy with an elder like Mr. B.G. Horniman when he reviewed and praised the picture.

ORSON WELLES?

A little discreet inquiry revealed to us that every word of the beautiful, idiomatic and forceful Hindustani dialogue of Gvalan was written by Baburao Patel. It was an unpleasant shock to many but so is Baburao's towering personality and since none of us can do anything about either let us gracefully accept the unique versatility of the man. Hollywood has a similar headache in Orson Welles. He, however, acts in his pictures. Baburao may also do so some day. You can never trust him in such things.

SUBTLE TOUCHES

The story of Gwalan is the usual boy-meets-girl theme with several topical aspects very subtly interwoven. This is perhaps the first time that the scion of an aristocratic family actually marries a commoner without sacrificing her for a girl of his own status as we usually see on the screen.

In protecting his slove for the poor heroine, the hero is made to speak many a dialogue which sounds at once humanitarian and socialistic. The son's defiance of the father's tyranny becomes a vivid episode of socialism in practical life.

Again in a very subtle manner is emphasised the loyalty of the Muslim servant of the family who is called "Chacha" all along by the prince and from whom is sought even the blessing after the wedding. The sequences in which the Muslim servant appears emphatically contribute to prove the interwoven pattern of traditional Indian life in which the Hindus and the Muslim fail to distinguish each other and sigh and smile with the same face through a common heritage.

The scene in which the village butcher refuses to buy the heroine's cows on grounds of a good neighbourhood is another suggestion that even Muslim, however fearsome they may look today, are human beings with instincts of the neighbourhood.

Well, Gwalan has many progressive angles but Baburao Patel's art of writing and direction has made them subtle suggestions and not blatant preachings, which probably would have become objectionable.

CINDERELLA STORY

Gwalan has a hackneyed Cinderella story in which a poor village milkmaid meets the local prince and both falls in love with each other. The prince has another girl from his own class of society kept ready for him, but beauty and rustic simplicity take him to the village girl.

Scandal soon provokes the rich girl to persecute the poor and the father of the hero misuses his authority and tyrannizes the lovers. Some utterly unimaginable and unusual scenes constitute the climax, in which the old tyrant turns a new leaf with the help of his faithful Muslim servant and accepts the village maid as his daughter-in-law. It ends well, though unusually, seeing that a prince takes a commoner for a wife.

Most of the thrill of the story is in its fast and unusual development, The drama has a terrific speed from the beginning to the end and even the songs seem to contribute to the thrilling drama that is unfolded on the screen.

The dialogue is exceptionally good and pointed. It has both idioms and ideas. The songs of Pandit Indra sound refreshingly new and different this time and they are very attractively tuned by Hansraj Bahel. The sound reproduction, however, is not so happy in Krishna though the photography seems attractive in spite of a badly processed copy.

Mr Patel's technical direction is, as usual, in advance of the times. He has always something new to teach in the use of the camera and Gwalan is outstanding proof of Mr Patel's technical knowledge.

The emotional part of the story is superbly directed and almost every situation reveals the director's unique understanding of human psychology. All this, however, is expected from Mr Patel and no special compliment is meant while recording this fact.

The village atmosphere in the story is very effectively portrayed with the familiar local characters which contribute to making our village life what it has always been. In fact, al the village scenes are so realistic that one feels like being a spot observer while seeing the pictures.

We still feel that Mr Patel could have taken a purely progressive theme in place of Gwalan.

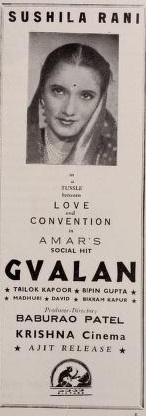

SUSHILA RANI'S SOMERSAULT

From the players, Sushila Rani, who gave a stoic and dignified performance as Draupadi, does a complete somersault as Shyama, the milkmaid. No one ever suspected the usually calm and Queenly Sushi'a Rani of playing a coquettish milkmaid in early parts. She sings, dances and flirts with an abandon that is at once artistic and romantic. Her histrionic genius is however, revealed with great effect in the pathetic situations in the concluding reels of the story. With her superb emotional portrayal, she moves the audience to tears and wins the sympathy of everyone in the vast crowds. Sushila Rani, who is a highly accomplished musician, sings her songs with perfect melody and rhythm in a voice which thrills the audience with its excellent timbre and natural sweetness.

Next to Sushila Rani, Bipin Gupta provides a great dramatic base to the story in the role of the Raja Saheb. the tyrant. Though this portrayal seems to have been purposely overdone and made stagy. Bipin Gupta's work remains a highlight of the picture. The writer has put fiery words in his mouth which shake the nerves of the audience. The man lives the role of the tyrant and proves his great histrionic art under strong direction.

David plays "Kallu", the devoted family servant with proverbial wisdom and patience. David eclipses all in his long charge-sheet during the climax and once again proves, after his classic portrayal of Shakuni, that he needs only Baburao Patel's strong direction to bring out the best in him.

For the first time in his long career, Trilok Kapoor looks and plays the hero effectively. Even his diction is more regulated and one can hear his words distinctly in Gwalan. Trilok makes a good team with Sushila Rani and one feels like having met a Rathod when he sees Trilok in Gwalan.

The surprise packet of the picture, however, is Sheikh Hassan. He plays Mohan and in doing so tickles the audience continuously by giving a completely successful and sympathetic portrayal.

Madhuri, in the role of Sheela, plays her time-honoured role superbly and provides the necessary dramatic contrast to the drama. Nagendra plays the village barber and a better on is difficult to imagine. Bikram Kapoor plays the heroine's father and looks a village milkman every inch.

In fact, every one plays so well and every little item is so carefully attended to that it is difficult to find faults with the picture and the portrayals which all again boils down to praising Baburao Patel-when is the only unpopular aspect in the eminently successful picture Gwalan.

Jealousies apart, let us for once state that Baburao Patel has done an exceptionally good job of Gwalan and the picture entertains every second with a speed that is unusual on the Indian screen. (And I hope I am not pilloried for this review, which incidentally, is what I honestly feel about this picture, in spite of Baburao's fame and fortune.)

This review was originally published in Film India's 1948 issue. The images used were not part of the original article and are taken from Film India and Cinemaazi archive.

.jpg)