My Shakespeare Favourites in Cinema: Ranjan Ghosh

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

Ranjan Ghosh’s Hrid Majhare, based on three plays of Shakespeare, heralded a renewed interest in the Bard in Bengali cinema. The film-maker spoke to Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri about his favourite film adaptations of Shakespeare.

Introduction

Over 400 years since William Shakespeare wrote his plays, they remain a perennial favourite with Indian film-makers. A number of reasons have been put forward for this, including India’s history as a colonized nation, its education system that prioritized English texts, an Oriental fascination with Western masters, the universality of the Bard’s characters and the human conditions they represented, the influence of Parsi theatre which drew heavily from the Bard, among others.

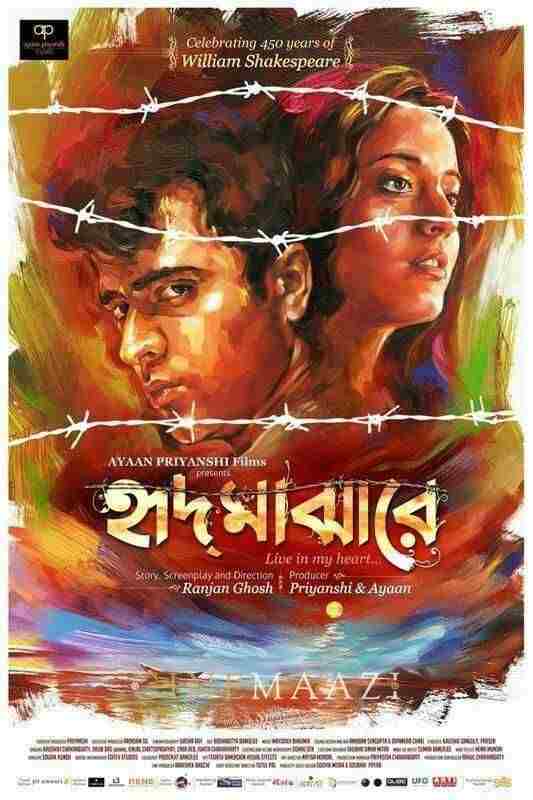

The film starred Bengali heart-throb Abir Chatterjee as Abhijit, a mathematics teacher who falls in love with a doctor (Raima Sen). An ominous meeting with a soothsayer leads to a chain of events where, much like the Bard’s Othello, Abhijit loses his bearings, changing from his rational, scientific self to someone who develops a fetish for random chance, leading to tragic consequences.

Interestingly enough, Hrid Majhare was followed by a spate of Shakespeare adaptations in Bengal. These included Aparna Sen’s Arshinagar (2015, based on Romeo and Juliet), Anjan Dutt’s Hemanta (2015, based on Hamlet), Srijit Mukherji’s multi-starrer extravaganza Zulfiqar (2016, Julius Caesar and Antony and Cleopatra). By far the most critically feted of these recent adaptations, the film went on to feature in a 2016 conference on ‘Indian Shakespeares on Screen’ organized by the British Film Institute and the University of London. In the same year, Oxford, Cambridge and the Royal Society of Arts (OCR) Examination Board enlisted the film in the syllabus for its A-Level Drama and Theatre course – the only other Indian film to feature besides Vishal Bhardwaj’s Omkara.

Ranjan Ghosh’s Picks

Gunasundari Katha (Telugu, King Lear), Kadiri Venkata Reddy, 1949

I have chosen this film because of its historical significance as the first direct adaptation of any Shakespearean work in India. K.V. Reddy took up a great tragedy and turned it into a full-length entertainer with a happy ending. The film became an astounding success. Reddy skilfully blended fantasy with mythology. The photography was by none other than Marcus Bartley, the famous Anglo-Indian cinematographer, known to have shot films like Maya Bazar and Chemmeen. The musical score by Ogirala Ramachandra Rao was a big hit then. There is a story behind Reddy opting for a bear into which the hero is turned owing to a curse. During his schooldays in Tadipatri, he had once gone to the nearby Nallamala forests with his friends. Spotting a bear at a distance, all the boys threw stones at it. But not Reddy. The angry bear charged towards the boys who ran for dear life. After chasing them for a while, the bear returned to find Reddy standing and shivering in fear. The bear simply looked at him and moved away. In an interview, Reddy had said that he realized that not only humans but animals too have feelings. He remembered the kind-hearted bear and made it a character in Gunasundari Katha. He had truly turned King Lear into his own creation!

.jpeg/images%20(13)__452x600.jpeg)

This is a landmark film by one of my favourite film-makers. Even thirty years after its release, it remains unbearably sad to watch. What I like the most is the way it breaks the Hollywood stereotypes of a mechanical plot and the hero’s journey. It’s a road movie-cum-romantic comedy about such forlorn characters. It is about gay hustlers drifting, and as a testimony to the director’s sheer brilliance, itself seems to be without direction initially. It drifts from one casual encounter to the next, getting what it can from the passing connections, some of them very funny, others harrowing. And when the film abruptly reaches its end, the conclusion is seen, in hindsight, to have been inevitable from the opening frame. Photographed by Eric Alan Edwards and John Campbell, My Own Private Idaho has a beautiful autumnal look and a way of seeming to take its time without actually wasting it, a hallmark of road movie looseness. Shots of lonely highways, condemned buildings, landscapes and natural phenomena suggest the internal lives of the characters. And what unforgettable performances by Keanu Reeves and River Phoenix!

.jpeg)

Justin Kurzel’s sensory and visceral storytelling makes this adaptation of Macbeth a favourite of mine. Kurzel goes his own cinematic way, borrowing from the Bard when he chooses to, and throwing away important passages at other times to make room for those gloriously stinging visuals (shot by Adam Arkapaw). His directorial mettle is imprinted on his masterful and boldly rogue visionary design of the epic film. As you watch, you know that this is quintessential Shakespeare, and yet Kurzel has managed to make it his own. Speaking of performances, Michael Fassbender’s is an exceptionally fine act. Quietly, assuredly and insistently, the brutally handsome and well-cast actor pulls you to him in scene after scene, and with restrained intensity. He is matched superbly by Marion Cotillard as Lady Macbeth. She spews fire and ice and is supremely haunting and enigmatic.

.jpeg)

This is a must-watch, a compelling adaptation of the Bard’s Othello for the first time in India. Under Jayaraaj’s able direction, the story took on a life of its own, and Kaliyattam became more than just an adaptation of Othello, making us take a fresh look at the age-old tragedy. The film was anchored in the mystical, ritualistic Theyyam, one of the oldest indigenous art forms of north Kerala. This gives it a folksy feel. What also drive the film are the superlative performances by two of Malayalam cinema’s best: Manju Warrier and Suresh Gopi (who won the National Award for Best Actor). I was amazed by the conviction with which Manju Warrier played her Desdemona. The cinematography was in sync with the prevailing mood of the narrative and did not slide into vacuously beautiful frames and compositions. Seamless editing and an efficient soundscape were aided by Kaithapram’s music. Borrowed heavily from Theyyam, it enthralled me with its unobtrusive compositions, and story-like lyrics. Jayaraaj richly deserved the National Award for Best Director.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Ran remains my most favourite Shakespeare adaptation. Here was a master at his creative best, doing full justice to the genius of the Bard. This one is a textbook film for a lot of genres – the Western, war films, period dramas. What an inspired use of colour, motion and sound! This is probably Kurosawa’s greatest ode to German Expressionism. The way the film has been mounted, its physical scale, is awe-inspiring and overwhelming. Kurosawa’s deployment of huge armies in vast landscapes displays a pre-digital mastery that we can only gasp at today, and the magnificent castle siege sequence – arrows flying, blood flowing, stage crimson – is what we dream to achieve all the time! Ran is impossible to forget, not because of the dazzling battle scenes; nor, of the bloody repercussions of violence from a battered warrior clutching his dismembered arm to a devious wife; nor, simply the vivid, ferocious performances. It is the entirety of its achievement, the humongous size of the production, both physically and in its drama that seizes one so tightly. The title translates as ‘chaos’ but Kurosawa proved with Ran that he was and still is the ultimate master of control.

Tags

About the Author

Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri is either an 'accidental' editor who strayed into publishing from a career in finance and accounts or an 'accidental' finance person who found his calling in publishing. He studied commerce and after about a decade in finance and accounts, he left it for good. He did a course in film, television and journalism from the Xavier's Institute of Mass Communication, Mumbai, after which he launched a film magazine of his own called Lights Camera Action. As executive editor at HarperCollins Publishers India, he helped launch what came to be regarded as the go-to cinema, music and culture list in Indian publishing. Books commissioned and edited by him have won the National Award for Best Book on Cinema and the MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Images) Award for Best Writing on Cinema. He also commissioned and edited some of India's leading authors like Gulzar, Manu Joseph, Kiran Nagarkar, Arun Shourie and worked out co-pub arrangements with the Society for the Preservation of Satyajit Ray Archives, apart from publishing a number of first-time authors in cinema whose books went on to become best-sellers. In 2017, he was named Editor of the Year by the apex publishing body, Publishing Next. He has been a regular contributor to Anupama Chopra's online magazine Film Companion. He is also a published author, with two books to his credit: Whims – A Book of Poems (published by Writers Workshop) and Icons from Bollywood (published by Penguin Books).

.jpg)