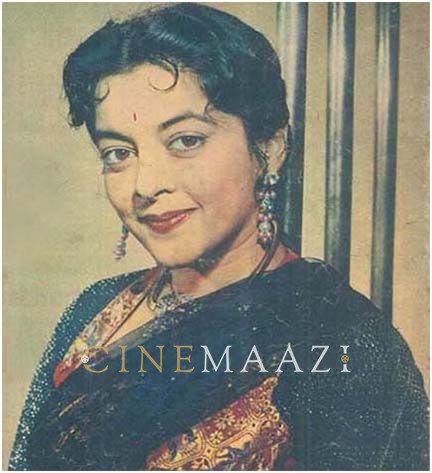

"If I had my way I would forget the sad moments of my life and cherish only the happy ones."

My life is like a rich fabric woven with incidents– happy and sad, sparkling with laughter and filled with tears. The surface of the fabric is patchy. Some portions of it are as good as new, so vivid they are. Others are faded and old, for their substance has retreated down the dusty corridors of memory.

Remembering is not a matter of volition–one cannot choose what one would like to remember and what one would like to forget. The most trivial incident has a knack of cropping up unexpectedly.

But if I had my way I would like to remember only the happy moments of my life and forget the sad ones. It is said: "Laugh and the world laughs with you; cry and you cry alone."

I am tolerant and forgiving, and I am inclined to accept anything that befalls me with resignation. I am not one of those who make a show of their grief before people who are likely to be impatient about it.

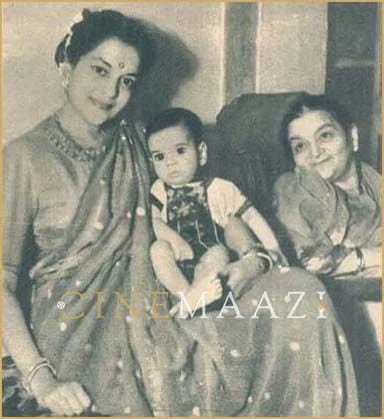

My earliest memories are of my mother, who died recently. We loved each other deeply. I will never forget the night she woke suddenly in the middle of the night and shook me awake. I was seven at the time.

"Are you all right?" she asked anxiously, touching my head, feeling me. I was sleeping beside her.

She had had a bad dream in which she saw that I was involved in a terrible accident. The dream was so vivid that even when she awoke and saw me beside her, she could not quite believe that no harm had befallen me. I was struck by her anxiety and deep love for me.

As a little girl, I was very fond of singing and dancing, and some early memories are of incidents which concern my proficiency in them. At the age of six or seven I took part in the very first Children's Programme broadcast over All India Radio. I sang in that programme and won the first prize for my singing.

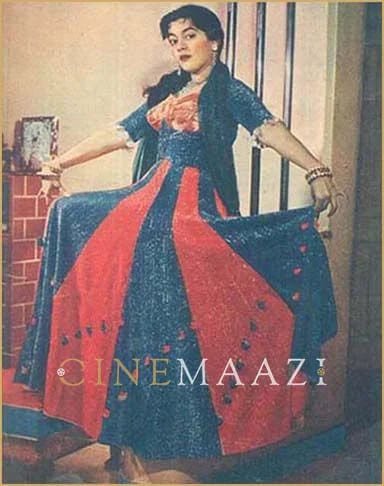

A year later I took part in a fancy-dress competition organised by the Sudharna Sangh. The competition was held at the Cowasji Jehangir Hall and was presided over by Mr B G Kher. Dressed as a gypsy, I approached him shyly and offered him a copy of the Programme. That evening I won the first prize and it was a happy moment when I received it from Mr Kher.

Unlike many other stars, I joined films by chance rather than by design. Although I was good at singing and dancing, I had no intention of becoming an actress. But during a school vacation a producer asked my father to let me work in a devotional film. My father agreed, thinking I could spend the holidays usefully.

I was the pet of the family, and had never been scolded even by my parents. Therefore, the first time I was scolded was to me a moment of extreme humiliation-more so because I was scolded in the presence of so many people!

I was working in my second or third film. That day, a shot was not working out to the director's satisfaction. He suddenly lost his temper and began to shout at me. He ridiculed me, saying I did not know how to act, or speak my lines! I was so humiliated. I bit my lip to check my tears.

I was hurt and I was angry too. But I put over a good performance and the shot turned out to be the best in the film. The moment I got home in the evening I wept bitterly, but I had my parents to console me.

I remember an amusing incident which happened in London. I had gone there with Producer-director S K Ojha for the shooting of "Naaz".

I was fascinated by London and thought it would be a good idea to see the big city from the upper deck of a bus. So I boarded a bus and took a seat. The conductor approached me and asked me where I wanted to go. I told him and gave him the money. He gave me the change-more than was due to me! In a moment I learnt the reason. He gave me a "half ticket! I didn't know whether to feel surprised, embarrassed, or take it as a compliment!

From London, the unit went to Cairo, and I with it. Between spells of shooting we went sight-seeing. On one occasion we visited a mosque. I saw a handful of people coming out of it. Seeing me, they stopped.

"You are an Indian?" one of them asked.

"Yes," I said. "Why?"

I must also tell you about a disaster which was averted. We were location shooting at Bassein for "Bharti. For the scene Ajit, my co-star, and I were to swim towards a boat. In another boat were the camera and crew. As soon as the camera was switched on, Ajit and I jumped into the sea. The sea was rough, and we were being carried further away from the boat towards which we were swimming. I was numb with fear and felt certain that death was at hand. Fortunately, two fishermen, who were in a boat some distance away, saw my plight and swam to my rescue.

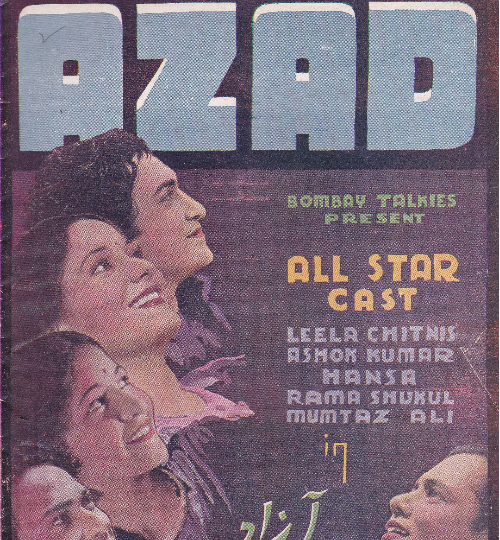

I will never forget the three years during which I did not work in any film. It was in "Samadhi" that I staged a come-back and everybody had taken for granted that my career in films was over. It was a time of trial and frustration. Offers were made to me for featured and minor roles. But I refused them all.

My self-confidence was at its lowest ebb when "Samadhi" came along. When I reported for work, it was as if I had awakened from a long sleep. I felt as though I was starting all over again, like an artist new to films. I will never forget the first two days on the sets. I was getting more and more worried. Was my work bad? Had I lost the "feel" of acting? Why was everybody so glum and unresponsive and silent? No one on the set had a word of encouragement for me. I was convinced they thought my work was below the mark. They had not seen the rushes. When they did, their faces were wreathed in smiles. They said, "Nalini, you're wonderful!"

In my entire career, it was the most sorely-needed praise.

During the making of "Samadhi," a night shooting session went on till four o'clock in the morning. I was about to get into my car when something "stung" me in my ankle. Bending down, I touched my ankle, and saw blood on my fingers! At once, I began to cry: "Snake! Snake! I've been bitten! I'm dying!"

Everyone from the studio came running, flashing torches and looking for the reptile.

They found instead an old, rusty wire which had pricked me! As soon as I saw it, I burst out laughing. I learnt that fear, more than poison, can kill people, and that he who conquers fear conquers evil.

I am reminded of the operation I underwent a few months ago. Fear of death was present only so long as I was conscious. Once the chloroform began to act and I drifted into unconsciousness, fear ceased to exist. Then, when it was all over and I came to, it seemed as though nothing had happened. "Why, it was nothing. Why was I so afraid?" I asked myself. Nevertheless, one of my greatest moments of happiness was when I fully returned to consciousness.

I do not think sensitive people who nurse their sorrows are wise in laying their hearts bare to their friends, for I sincerely believe that friends are not as interested or sympathetic as they seem to be. I have had my share of sorrows in life, sorrows about which I do not like to speak, much less write. I prefer to dismiss them, or relegate them to the back benches of remembrance with a philosophic shrug.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's 31 January 1958 edition.

About the Author

.jpg)