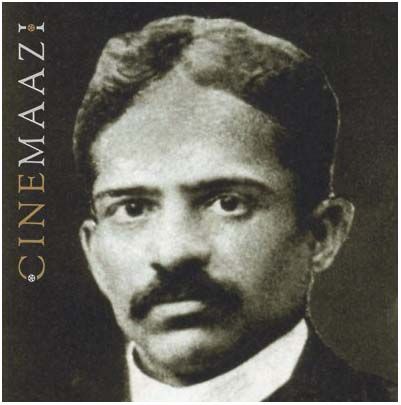

Dadasaheb Phalke

- Real Name: Dhundiraj Govind Phalke

- Born: 30 April, 1870 (Trimbak, British India)

- Died: 16 February, 1944 (Nashik)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

- Parents: Dwarkabai, Govind Sadashiv Phalke

- Spouse: Saraswati Phalke

- Children: Bhalchandra Phalke , Mandakini Phalke

Considered the father of Indian cinema, Dhundiraj Govind Phalke, better known as Dadasaheb Phalke, is credited with birthing film production in India, which, over the decades, swelled into a mammoth industry over various centres across the country. Making the country’s first indigenous feature film, his debut film, Raja Harishchandra (1913), is hailed as India's first full-length feature film. In the course of his career that spanned 19 years, Phalke made 95 feature-length films and 27 short films. These include Mohini Bhasmasur (1913), Satyavan Savitri (1914), Lanka Dahan (1917), Shri Krishna Janma (1918), Kaliya Mardan (1919), Sairandari (1920), and Shakuntala (1920). The Government of India instituted the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, awarded for lifetime contribution to cinema, named in his honour.

Born Dhundiraj Govind Phalke on 30 April, 1870, in Trimbak, British India, now in Maharashtra, he was one of seven children born to Dwarkabai and Govind Sadashiv Phalke alias Dajishastri, a Sanskrit scholar who officiated as a Hindu priest at religious ceremonies. The family moved to Bombay after his father was appointed professor of Sanskrit at Wilson College. Completing a one-year course in drawing from the Sir J J School of Art in 1885, Phalke joined Kala Bhavan, Faculty of Fine Arts, at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. Here he completed a course in Oil painting and Watercolour painting in 1890, besides achieving proficiency in architecture and modelling. Around the same time, Phalke started experimenting with photography, processing, and printing. Winning a gold medal for creating a model of an ideal theatre at the 1892 Industrial Exhibition of Ahmedabad, he was also gifted a good camera by a fan. Completing a six-month course in techniques of preparing half-tone blocks, photo-lithio, and three-colour ceramic photography, he was sent by Principal Gajjar of Kala Bhavan to Ratlam to further learn techniques under Babulal Varuvalkar.

In the early stages of his career, he started an engraving and photo printing business. However, turning professional photographer in 1895 did not bring much success owing largely to the misconception that being photographed would suck the energy out of a person and lead to bad consequences. Phalke even had to try hard to convince the Prince of Baroda to acquiesce to be photographed. He then moved to painting stage curtains for drama companies, which not only gave him basic training in drama production but also garnered him a few small roles on stage. He also picked up magic tricks from a German magician who was touring Baroda at the time. By the end of 1901, Phalke began to conduct magic performances in public using the name Professor Kelpha, a combination of the letters of his last name. Bagging employment as a photographer and draftsman at the Archaeological Survey of India in 1903, he however resigned three years later and set up a printing press in Lonavala with R. G. Bhandarkar as partner. Eventually, due to differences, Phalke quit the partnership.

The turning point came in April 1911 (some sources claim it was 1910), when he watched a film along with his older son Bhalchandra. It was Amazing Animals at the Girgaon movie theatre, America India Picture Palace. Returning home, the boy talked about the animals they had seen on screen—only none of the others believed him! It led to Phalke taking the entire family the next day over to the movie theatre. Being Easter, director Alice Guy-Blaché’s Jesus, The Life of Christ (1906) was being screened. It sparked within Phalke the desire to make a ‘moving picture’ on the Hindu deities, Rama and Krishna. He devoted an entire year to learning about film and collecting film-related books and movie-making equipment from Europe. He burned the midnight oil watching films for four to five hours each evening, buying a small film camera and reels and projecting the images on a wall. Sleep-deprived, eyesight ravaged, he struggled to accumulate the finances to go to London to acquire technical knowledge of filmmaking. Mortgaging his insurance policies, he managed to secure Rs.10,000, and left for London in February, 1912. The Editor of Bioscope Cine Weekly, which Phalke subscribed to, introduced him to filmmaker Cecil Hepworth of Walton Studios. He thus gained entry into the studio’s various departments. Two weeks later he set off on the journey back, bearing the Williamson camera he had bought for 50 pounds, and having placed an order for Kodak raw film and a perforator. He founded Phalke Films Company on the day he returned to India—1 April, 1912.

A short film he made demonstrating the growth of a pea plant (Ankurachi Wadh) helped him prove his filmmaking techniques as well as attract financiers. With Yashwantrao Nadkarni and Narayanrao Devhare offering Phalke a loan, he penned the script of a film based on the legends of Raja Harishchandra. Casting Dattatraya Damodar Dabke as King Harishchandra and Anna Salunke—a young male actor as Queen Taramati as women were not open to acting in films, and his own son Bhalchandra as the prince Rohitashva, Phalke assigned the cinematography to Trymbak B Telang. He himself would handle the script, direction, production design, make-up, editing, and film processing over the six months and 27 days that it took to shoot around four reels i.e. 3,700 feet of film.

Raja Harishchandra premiered at Bombay’s Olympia Theatre on 21 April, 1913, releasing on 3 May, 1913 at the Coronation Cinema, Girgaon, Bombay. A commercial success, it was acknowledged as India’s first full-length feature film. Relocating to Nasik, Phalke worked on the mythological love story of king Nala of Nishadha, and Damayanti, princess of Vidarbha. With a delay in start of filming, he moved on to working on Mohini Bhasmasur, on the mythological story of Mohini, the female avatar of the Hindu god Vishnu, and Bhasmasura, an asura or demon. When a travelling drama company, Chittakarshak Natak Company, visited Nashik, Phalke managed to convince its proprietor, Raghunathrao Gokhle, to allow two of their actresses to act in the film. Thus, did Durgabai Kamat cast as Parvati and her daughter Kamlabai Gokhale as Mohini, become the first women to act in the Indian cinema. Released on 2 January, 1914 at the Olympia Theatre, Bombay, the film was well received, as was Phalke’s next, Satyavan Savitri which released on 6 June, 1914.

A hat-trick of hits enabled Phalke to clear his debts as well as visit London again to buy electronic machinery worth Rs.30,000. Impressed by his three films which he carried to London, various studios wished to hire Phalke to produce films in England. Returning to India, trouble awaited with World War I looming and his investor cutting funds for his studio. Struggling to collect capital for his next, Raja Shreeyal, he undertook a tour of princely states, collecting the amounts from various heads of kingdoms as payment for his shows.

Remaking Raja Harishchandra as Satyavadi Raja Harishchandra (1917) after its negative went missing, he also made a documentary, ‘How Movies Are Made’, demonstrating the process of filmmaking to potential investors. Helped by an appeal made by Lokmanya Tilak, Phalke accumulated the capital to start filming Lanka Dahan. Released in September 1917, it portrayed the burning of Lanka in the episode from the Ramayana. A roaring success, with Anna Salunkhe playing both Rama as well as his wife Sita, in the first double role in Indian cinema, it lifted Phalke out of the quagmire of debt.

Approached by various businessmen desiring a partnership, Phalke eventually accepted the proposal of five Bombay-based textile industrialists—Waman Shreedhar Apte, Laxman Balwant Phatak, Mayashankar Bhatt, Madhavji Jesingh, and Gokuldas Damodar. Thus, was the Phalke Films Company converted into the Hindustan Cinema Films Company, on 1 January, 1918, with Phalke as a working partner. The studio’s Shri Krishna Janma, with Phalke's six-year-old daughter Mandakini playing the lead role of Krishna, released on 24 August, 1918, and went on to become commercially successful. Phalke's next film, Kaliya Mardan, depicting the killing of the poisonous serpent Kaliya, by Lord Krishna, released on 3 May, 1919 and also met with commercial success, running for 10 months.

Increasing and irresolvable differences with the partners of Hindustan Cinema Films Company eventually saw Phalke quit and announce his retirement, to depart with his family for Kashi. Watching several Hindi plays in Kashi, by the Kirloskar Natak Mandali, and interacting with the travelling theatre company’s officials, Phalke went on to write a Marathi language play, Rangbhoomi. He eventually staged the satire on stage conditions of its time, at Baliwala Theatre, Bombay in 1922, along with performances in Poona, and Nashik, to a lukewarm response.

Eventually, after resisting several offers to re-join the film industry, Phalke accepted an offer from the struggling Hindustan Cinema Films Company to join as a Production Chief and Technical Advisor. He went on direct Sant Namdeo, which released on 28 October, 1922, followed by other films. However, after a series of hiccups, Phalke finally resigned from the job. Setting up a new company, Phalke Diamond Company, he acquired capital from Mayashankar Bhatt, a former partner of the Hindustan Cinema Films Company, to start filming Setubandhan. The film was stalled after funds ran out during filming, leading to Waman Apte of Hindustan Cinema Films Company offering to bail him out. However, by the time Phalke’s silent film was ready for release, the world had changed. Talkies were the new rage. Setubandhan released in 1932, and was released again in 1934 with the addition of sound, on the recommendation of Ardeshir Irani, director of Indian cinema’s first sound film, Alam Ara (1931). However, even sound didn’t help the film’s fortunes. In between, he also wrote a Marathi play Rangbhoomi in 1922.

Phalke went on to direct his only sound film—Gangavataran, for the film company Kolhapur Cinetone, belonging to Maharaja Rajaram III of Kolhapur. Completed in two years at the cost of Rs.2,50,000, the film released on 6 August, 1937 at the Royal Opera House, Bombay.

Extremely conscious of the revolutionary change he was ushering into the Indian cultural sphere, he made efforts to link his cinema practice with the Swadeshi movement. His films are credited with being a major influence on the frontal framing that would dominate Indian cinema, later described as the ‘darshanic gaze’ by several scholars. Phalke’s innovative and enterprising spirit not only set the ball rolling for what would become the world’s largest film industry, but also left its mark on key aspects of film aesthetics, particularly the mythological genre.

After the death of his first wife in the bubonic plague epidemic of 1899, Phalke remarried Girija Karandikar in 1902, who was renamed Saraswati Phalke. He had seven sons and two daughters.

His advancing years saw Phalke withdraw from films altogether. Retiring to Nashik, Dadasaheb Phalke passed away on 16 February, 1944. It was the end of an era. He remains unforgettable for his devotion to filmmaking against all odds, and his enormous contribution to Indian cinema.

-

Filmography (54)

SortRole

-

Gangavataran 1937

-

Vasant Padmini 1929

-

Chandrahasa 1929

-

Malti Madhav 1929

-

Malvikagnimitra 1929

-

Sant Mirabai 1929

-

Vasantasena 1929

-

.jpg)