Film in Retrospect: Images Images

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

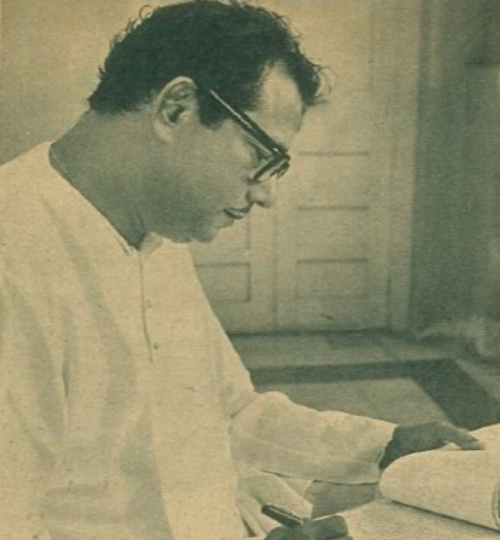

Guru Dutt's career as a director spanned between 1951 and 1959. Baazi was the first film he directed followed by Jaal, Baaz, Aar Paar, Mr. & Mrs. 55, Pyaasa and Kaagaz Ke Phool, which was the last film that had the direction credited to him. Most discussions of his work though necessarily include Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962), credited to his dialogue writer Abrar Alvi, which bore the unmistakable look and the preoccupations of his own vision.

What constituted this unique vision that made a Guru Dutt film instantly recognisable even when it did not bear his name? Almost at the exact centre of his career as a director, Guru Dutt made Pyaasa (1957). Pyaasa has more than just chronological significance. In its theme it epitomised Guru Dutt's deep felt anguish about life and about the struggle of the artist. It also crystallized a style of film -making that in fact had been evolving since Baazi.

From personal experience, Guru Dutt knew that this question is most often posed in the life of an artist with the further irony that society's evaluation of an artist may change overnight and quite unpredictably. The success that comes to him is not always because of the intrinsic worth of his works but often only because of chance. Thus in Pyaasa, we have the poet becoming successful because of the mistaken announcement of his suicide. From this arise two further Guru Dutt themes-one, the market culture of life where everything may be bought or sold and evaluated according to the price, and two, the basic antagonism that exists in social conditioning to the free flowering of life.

The Baazi gambler may not be a struggling artist but he is described as a free soul pursuiting gambling for the pleasure of exercising an uncanny talent But social needs force him into the straight-jacket mould of a crook. His only redemption is the deep love he has for his ailing sister. The Aar Paar taxi driver too is obsessed with the idea of freedom but finds himself being constantly enmeshed by other people's social ambitions. In Jaal, the world of the fishing village extends into its natural environs and nature. And Maria is the most loved offspring of this sylvan paradise. Tony appears in the midst of this bringing with him all the temptations of the big city including the lure of passion and romance. Maria is totally entrapped but rather than giving in, she, through strength of moral character and .through her own unshakable faith in herself, manages to lift Tony out of his moral and emotional indifference. Thus in a Guru Dutt film, life is often portrayed as stretched with this tension between one's individual nature and the warping pull of money.

In the midst of this medley there is Dev Anand. Although he is shown as belonging to the lower-middle class there is a suggestion in one dialogue that he and his family have seen better days.

Tony, the smuggler in Jaal is of course a total social outcast but in the world of Jaal, it is not social stratifications that matter but moral commitments. In Aar Paar, the garage owner is shocked that a man he employed off the streets could have the effrontery to woo his daughter. But as the hero (Guru Dutt) points out, just because he enjoys a low social position at the moment, there is no reason to suppose that he cannot rise in the future. If in Baazi the contrast was between the hidden immorality of the rich and the sincere feelings of the poor, the contrast in Jaal was between rural contentment and urban ambitions. The analogy between Tony and the proverbial serpent in the Garden of Eden is drawn very clearly in the film with more than one deliberate reference to him as the serpent.

What made Guru Dutt films memorable was not just his obsession 'with certain themes but the fervour and intensity with which they were portrayed on screen. In this context his own contribution as an actor was vital to his films. He had developed for himself an underplayed non-gesticulating style-how often he was seen on screen just walking or standing with his hands in his pockets-which combined with his rather vulnerable facial expression conveyed more eloquently than any carefully worked-out sequences could, the rather self-absorbed dreamer buffeted around by the vagaries of Fate. The romantic image of the tragic poet was his hallmark and because director and actor were so strongly identified with each other, it is how one thinks of him personally even today.

In Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam, the first shot of Bhootnath is taken from his back as he stands looking at the haveli. Jaba too is first seen from her back as she laughs on hearing his name. A silhouette is similar to a back in that it is an outline of a mass without many details. One example of the many uses Guru Dutt made of the silhouette is the scene in which Suresh Sinha and Shanti sit talking in the large empty studio in Kaagaz Ke Phool. Although Guru Dutt's form was melodramatic, his actors' performances were always low key. Thus the silhouette, the shadow across the face, the mute back were used like moments of silence on a sound track, or the blank areas of a canvas-so that many levels of meaning could well up rather than have the connotations limited by articulation.

Waqt ne kiya in Kaagaz Ke Phool with its atmosphere of unrelieved tragedy is used in the film at the point when Shanti and Suresh are discovering the depths of their feelings for each other when there isn't as yet any obstacle to their realizing a relationship. In fact it could have been used later after they have been forced apart by circumstances. The song itself would have remained just as memorable for its poetry and its music. But by Guru Dutt's use of it so early in the film, the song became more than just a lament of ill-fated lovers. It became less particular to Suresh and Shanti but instead expanded in its connotations to include the irreversibility of time the tragedy of man's desire for love and the bitter-sweet irony of life that was the director's dominant leitmotif.

To give another example of Guru Dutt's talent for the light and imaginative touch we have Johnny Walker's song in Mr. & Mrs. 55, Jane kahan merajigar gayaji. Johnny Walker suddenly describing rhythmic pirouettes starts opening and looking into desk drawers in his office while his typist girlfriend watches with testy curiosity. All we hear on the sound track are effects. There is a little exchange of dialogue with the girl friend before he walks upto a phone, dials a number and suddenly bursts into song into the mouth piece. The usual convention of an instrumental prelude to an approaching song has been replaced by Johnny Walker's stylized movements, a bit of staccato dialogue and the sound of the telephone dial. When the song does burst out, it manages to be both in tune with the preceding visuals and take us by surprise. Often Guru Dutt picturised his songs not on the central protagonists but on people who were outside of the mainstream narrative–construction workers, film extras, an itinerant toy seller, fisher folk, a sanyasini. In Pyaasa, one of its most famous songs Aaj sajan mohe ang laga lo, is picturised on a stray sanyasini, while Gulabo and Vijay are on a terrace above the street where the song is being sung. For the sanyasini, the song is a convention of her religious vocation, but for Gulabo the song expresses her deepest sentiments articulating what it would be impossible for herto express herself. In visual terms too, Vijay stands immobile and unmoved almost like an icon in a temple while Gulabo at his back moves hesitatingly forward or retreats timidly with mute appeal dominating every nuance of gesture and expression. In this way Guru Dutt managed to inject tremendous profundity of feeling into what might have remained either a simple love song or a conventional bhajan.

With great depth of bitterness, Guru Dutt exposed the environment in which he worked in Kaagaz Ke Phool. The false tinsel world of films, the greedy producers, the pressures of the box-office, the corrupting influences, the petty-minded stars and the unforgiving fans. That he still succeeded in making films in this environment that were suffused with a personal vision of life and at the same time reflected the social tensions and aspirations of the period, could have been possible only at great cost to himself. The influence of Hollywood and the American film was manifest in his work-the romantic, tough hero, the gangster environment, the slick fast-paced cutting, the ballroom rhythms and the studio settings. In Aar Paar particularly, the rather obvious narrative in a thriller mould set against the streets and Sights of Bombay, is obviously shot with great feeling for the metropolis. This was the classic Hollywood genre that managed to inject the experience of actuality to any concoction of events. Since the Bombay formula insisted on comedy, Johnny Walker and Tun Tun became permanent members of his unit. But again one can see in every comic sequence or character developed, an attempt to give it body and a specific social setting. Thus we have Johnny Walker playing at various times a Parsi gangster with a moral code, a press photographer often called on to keep his cartoonist friend monetarily afloat, the oil masseur of Pyaasa or a high society playboy. The use of Bombay Hindi too must have been both a highly perceptive comic touch and the symbol for thousands of filmgoers all over the country of the street-side resourcefulness of the conglomerate metropolis that Bombay was and is.

Since Guru Dutt did not work through realism but through melodrama and industry-dictated fantasies, this transparent technique that he evolved seems more appropriate than a technique that would have created a total illusion. The audience remained acutely aware all the time of the presence of Guru Dutt behind the camera while viewing his films. Which is perhaps why his films, in spite of the slick Hollywood technique and the obvious Bombay masala ingredients never became mere escapist fare.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's 16-31 March 1987 edition written by Lalitha Krishna.

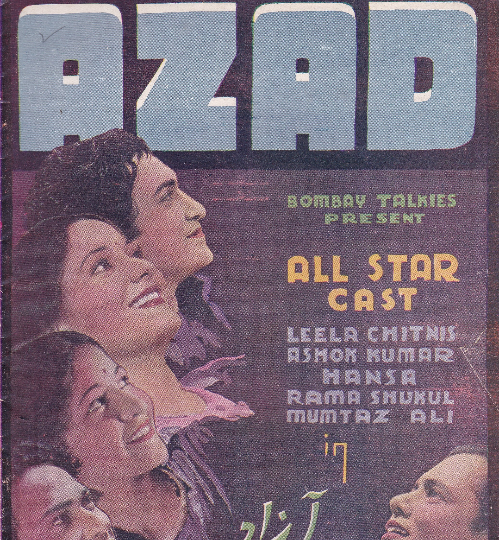

The images appeared are extracted from Cinemaazi archive.

.jpg)