Guru Dutt: The "Typical Hero" Tag Doesn't Fit

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

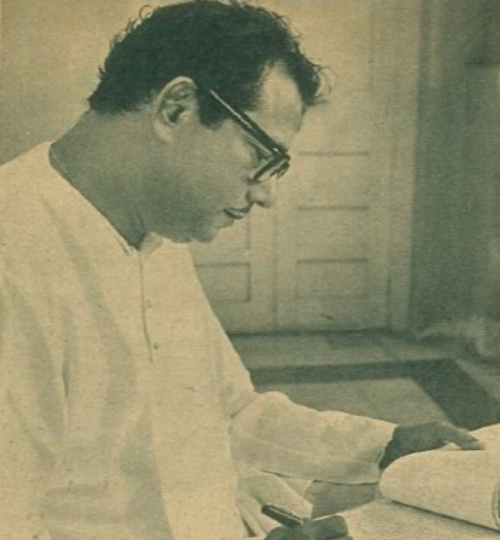

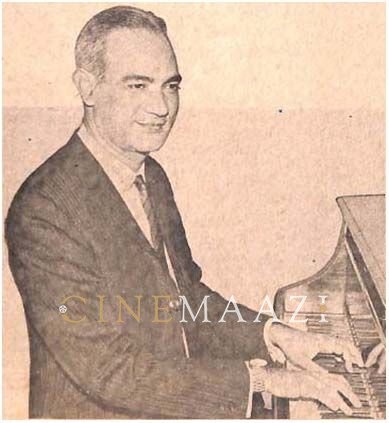

There is no use-denying that some of the most interesting film criticism today is being written in French. Whatever one can say against French critics they are usually one up on others, if not in theory at least in looking beyond geographical frontiers. Thus it is no real surprise that the first critical volume on Guru Dutt published outside India should come from France. It is a pity that the book, written by Henri Micciollo, is not available also in English, though its brief 55 pages do not really tell admirers of Dutt much that they don't already know.

Micciollo traces the image of Dutt as a destitute loner in his first films, in which he played bit roles as well as directing: as a bum in the first scene of "Baazi", as a Portugese fisherman in "Jaal". In this last film Micciollo attempts to make a case for Guru Dutt as a representative of the common man, the worker or the loner, and pushes this common man theme through almost all of the films, describing how he sleeps on park benches, dresses in rags, almost always isolated from society.

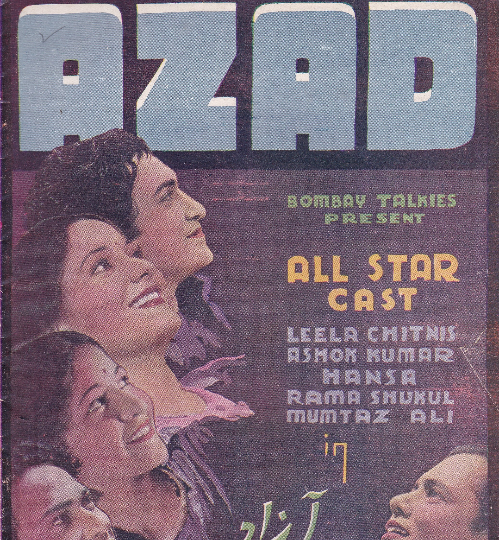

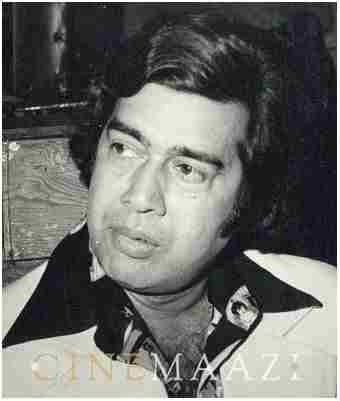

I was surprised to find that Micciollo gives so much space to a psychological portrait of Guru Dutt - something French film critics seldom do; they prefer to accept a good director blindly- and analyse all of his films as variations on one another. Here Micciollo tells us what Guru Dutt's other biographer, Firoze Rangoonwalla does not that he was reluctant to take the leads in his best films and would have preferred Dilip Kumar for "Pyaasa", Ashok Kumar for "Kaagaz Ke Phool" and Shashi Kapoor for "Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam". Micciollo eventually calls Guru Dutt "hypersensitive and impulsive", and tells us how he lost interest in several never completed films.

Still to Micciollo, and to all of us who like Guru Dutt as an artist, his films talk of "the place of the artist in society," and "Kaagaz Ke Phool" is Dutt's "8½", both films being about film-making. The film artiste, as opposed to the director, is more often chosen by chance and in "Kaagaz" Waheeda Rehman, like Dutt, "played in a way her true role." Micciollo finds the motion picture camera as menacing as a "drug" in the accidental introduction of Miss Rehman as an artiste in the story of the film and adds "in the end it (the cinema) will triumph over its creators," crushing them. He tells us that "the failure of the film is the ultimate vindication even of the theme of the film." One can easily agree with Micciollo and still be amazed at Guru Dutt's choice of a failing movie director as the central character without having to agree that this "menacing" quality is fully applicable to all cinema, or even all Hindi cinema.

What is least easy to swallow in Micciollo"s book is his attempt to make out that "Sahib, Bibi aur Ghulam" is the same kind of masterpiece as "Kaagaz" and "Pyaasa". He realises that in this film Dutt does not die nor reject the world as in the other two, but that here a society dies as well as most of the other characters, some by violent means.

Attempting perhaps to deny a certain personal detachment which I think makes "Sahib" a less interesting film than the others, Micciollo points out that Guru Dutt had by the time separated from Geeta Dutt and had already attempted suicide three times. He reminds us that Dutt never directed a film himself after the failure of "Kaagaz." He has something to say on how the directors were chosen. M Sadiq for "Chaudhvin Ka Chand" because he was Muslim, Abrar Alvi for "Sahib" because he was Bengali (but "Pyaasa" takes place in Calcutta also and for all that, Guru Dutt directed it).

Micciollo argues correctly that in "Pyaasa" the poet Vijay knows "a sort of posthumous glory." But is this true of the typical Indian hero, despite Hindu philosophy? He even quotes Sahir Ludhianvi's poetry to analyse all the director's important works, almost assuming that Guru Dutt wrote the poetry, ignoring the fact that it precedes "Pyaasa" by some 20 years. He also gives scant credit to music directors and cinematographers.

I am not French and Micciollo and I could eventually be accused, like certain other alien powers, of shooting each other down over Indian territory. So I will merely point out certain features of the book. Micciollo gives slight notice, much less than Rangoonwalla, to the effect of Satyajit Ray's international success on Guru Dutt's desires to take his films abroad. He tells us that Dutt saw "Pather Panchali" four times, but not how he felt about Ray. In addition he claims that Ray's success is only in regional cinema. (Rangoonwalla claims it was Dutt's frustration at Ray's success that led to his final disintegration).

After giving space to Dutt's psychology Micciollo still sees him as a "typical Indian hero ... in conflict with the society in which he lived. And from this came the essential theme of failure." To say that "the artist for Guru Dutt did not create for himself but for the public" is not an answer, though it is and perhaps always will be a question mark.

"Society" is a "fact" to Micciollo and if he eventually recoils from what he called Guru Dutt's essential affinity to the masses he cannot do anything in the end but constantly warn the (French) spectator that his films were essentially "melodramas", as are "all Indian films", and that Guru Dutt was highly influenced by American cinema. But was not Eisenstein influenced by Griffith?

The final limitation of the book is to see the film maker in terms of his society, attempting to tie the two together, sometimes with strings that don't exist. Beyond the term "melodrama" and oblique references to Hitchcock (a French favourite) and Fellini, he has ignored Guru Dutt's possible place in world cinema. But I would like to make my own comparison: Orson Welles.

"Kaagaz Ke Phool" recalls the sentimental material of "A Star Is Born" (3 American versions, none of them directed by Welles): it is the story of a film director who went spectacularly downhill with his public after a sensational beginning, as Welles and Dutt did. Guru Dutt was fresh from the success of "Pyaasa" when he started "Kaagaz." And Orson Welles, fresh from the notoriety he had caused with his radio programme based on H. G. Welles' The War of the Worlds-which had scared the pants off the entire United States- had carte blanche in Hollywood when he made "Citizen Kane." Both thus had temporary financial immunity from the "system."

In both "Kaagaz" and ''Kane'' the director is also the star, each playing a great man older than he is, who grows even older and dies; both films are told in flashbacks, although the flashback technique in "Kane" is more complicated than in the other. Kane harbours his secret yearning to regain his childhood in a broken sledge, and Suresh Sinha, the director in ''Kaagaz,'' keeps in his flat a doll not from his own childhood but from that of his only daughter; marital discord and a secondary romance form a background to both films.

In both films events are announced in newspaper headlines and in both there are films within the film-the newsreel summing up of Kane's life and Waheeda Rehman's "accidental" screen test. Both films use similar expressionistic lighting to convey mood rather than to present story information, like the shafts of light in the Thatcher Memorial Library in "Kane" and in the Ajanta Studios in "Kaagaz". The spaciousness of the sets and the fluidness of the camera movement in "Kaagaz" remind one of the spaciousness and the similar movement in Kane's private castle of Xanadu.

Neither film fared well at the box-office when it was first released but now both are considered among the finest films produced in their respective languages-"Kane" has become a classic in film societies in the United States and "Kaagaz" at morning shows in India. "Kane" has been singled out for individual study at the Poona Film Institute; and ''Kaagaz'' through Micciollo's own efforts may be one- of the first old Hindi films to receive serious attention in France, after the FFC's fine week of new Indian films there in 1974.

The only other important work in French on Indian cinema is P. Parrain's Regards sur Ie cinema Indien (Looking at Indian Cinema, editions du cerf, Paris, 1969), a somewhat sketchy 380 page book, tracing the high points of recent Indian cinema history and describing the season of 1967-8 when Parrain was here on a grant from a committee headed by Ingmar Bergman. The book gives Dutt about 14 pages. Barnouw and Krishnaswamy's 300 page Indian Film, Bombay, 1963) in a gigantic lapse of taste does not mention Dutt at all.

It is only fair to mention that Micciollo's volume contains a few misprints-I counted three-although far fewer than the absolutely unproofread monograph by Rangoonwalla produced by the Archive. The binding of the French volume is also superior, 30 folded pages stapled together, the glued cover of my Rangoonwalla came unstuck before I finished it. But I have no fear of dropping Micciollo's little book into my breast pocket in the Archive Library (one of the few locations where it is available in India), sneaking out with it and keeping it over my heart, whatever its faults, for years to come.

This article was published in 'Filmfare' magazine's 12-25 December 1975 edition written by Lyle Pearson.

The images and their captions appeared are taken from the same article.

About the Author

.jpg)