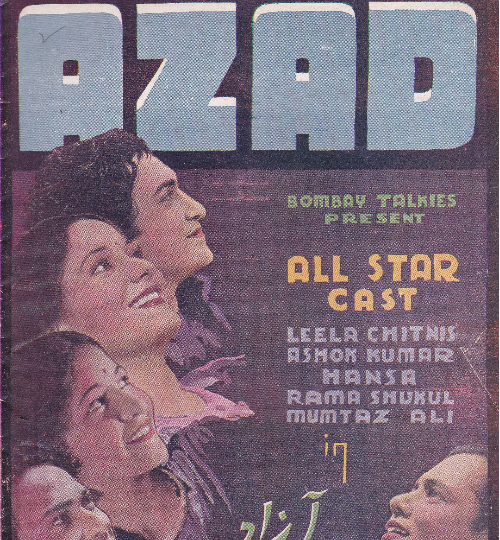

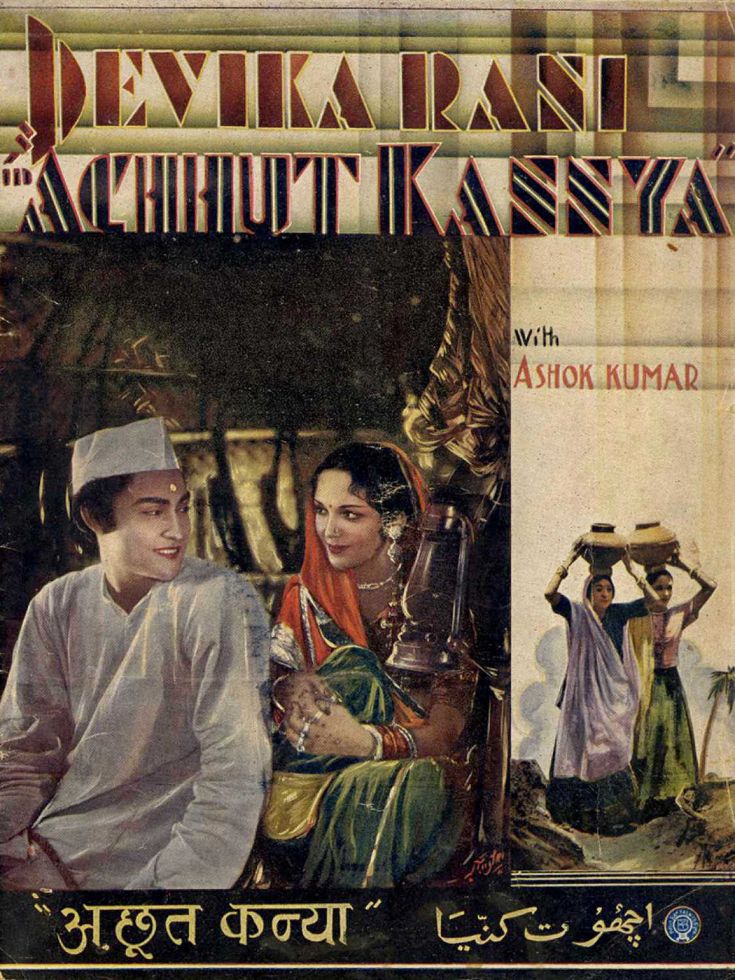

Achhut Kanya is a masterpiece by one of India’s pioneering film studios - Bombay Talkies. Bombay Talkies was founded by Himanshu Rai and the first lady of Hindi cinema, the ethereal Devika Rani. The couple along with the screenwriter Niranjan Pal and German director Franz Osten were pioneering figures in the Hindi film industry. As a ‘92-born, I haven’t watched too many black-and-white films. Though the few I have watched were classics like Pyaasa (1957), Mother India (1957), Woh Kaun Thi? (1964) which have left a deep impression upon me.

Mohan is shown as a progressive Brahmin, who not only forgives Dukhia for touching him, makes him a lifelong friend out of gratitude. This is how Kasturi and Pratap - their daughter and son respectively end up becoming childhood friends - they grow up together, play together. Mohan’s wife does not approve of this friendship, especially when the two of them become of marriageable age. Without any further delay, she gets Pratap married to a girl of their caste, and does not accept the dowry offered - which is quite progressive for the time. But even this “progressive” gesture backfires as Mohan had promised Dukhiya that he would pay Kasturi’s dowry with whatever he received from Pratap’s dowry. Pratap’s mother accuses of his father worrying for Kasturi more than Pratap.

Things take a turn for the worse soon after Pratap’s wedding when Mohan takes an ill Dukhia to his home so he can take care of him. An angry mob, instigated by Babulal Vaidya, a jealous rival medic chastises Mohan for bringing in “impurity” into the neighbourhood, moreover into his house. The angry mob proceeds to attack and injure Mohan and put his house on fire. Dukhia despite being ill, runs to his rescue and when he sees Mohan is hurt and unconscious, he runs to stop the next train so he can bring the railway doctor. For this he loses his job, and is replaced by Mannu.

It becomes known that Mannu is already married but had abandoned his first wife because her parents do not let her leave the house to live with him. The first wife, Kajri comes to the village where Kasturi and Mannu live and demands her rights to be reinstated as the first wife. Though Mannu is against it, Kasturi welcomes her and tells her it is her right to live with her husband and that she would never come in between them. This altruistic act by Kasturi shocks everybody who expected her to fight for her right as the only wife since it is clear even Mannu prefers the beautiful Kasturi to Kajri.

The climax of the film involves a venomous plot designed by Kajri and an unwitting Meera, Pratap’s wife. The idea is to make Mannu believe that Kasturi is having an affair with Pratap. They decide to do this by taking Kasturi to a fair in the neighbouring village and abandoning her there. They came back to the village and reported to Mannu that Kasturi refused to come back with them as she wished to run away with Pratap. An enraged Mannu attacks Pratap at the railroad crossing, as Pratap and Kasturi are returning from the fair. The two begin to fight, just as an unscheduled train is coming toward them. Kasturi gives up trying to stop them fighting and runs towards the train in the hope to stop, sacrificing her own life in the process.

The characters are shown as quite progressive for the times they live in. Mohan and Dukhia’s friendship paves way for Kasturi and Pratap’s friendship - a man-woman friendship which must have been a rare sight in the 30’s. It was a time the husband was referred to as Malik which literally translates to master or owner.

Kasturi’s sense of responsibility has been ingrained in her by her father, Dukhia, who has trained her in giving signals to trains, and remarks “the lives of many depend on us, it is our duty to protect those lives”. The lives of others have always meant more to Kasturi than her own. I believe this is why she holds no bitter feelings towards Pratap even when he gets married to another woman’s he prays he gets a “good wife”- and he reciprocates the feeling. Their sweet farewell to each other really stayed with me - I understood it as a sign of their unconditional love for one another that neither felt jealous or possessive of the other. But neither does she accept his proposal of eloping later when he realises his feelings towards Kasturi are more than platonic. She is unable to accept even though she loves him with all her heart, because she is aware of how this decision will affect all those to whom their lives are attached - Mohan, Pratap’s mother, Dukhia, Pratap’s bride. She is aware society will never accept them as a married couple - she remembers the riot that took place in the village simply because her sick father was taken into a Brahmin’s house. It is this selflessness that does not let her think twice when her husband’s first wife shows up - she welcomes her home and gives up her own rights as the rightful wife.

The film is set in India under British Raj, which might explain how Dukhia has a job, despite his caste origins. He is an employee of the Railways, a colonial contribution to India. It is this symbol of modernity that allows Dukhia and Kasturi to live a life of dignity, a right often denied to the dalit community even today.

Tags

About the Author

Rachna Ramesh Kumar is a media consultant based out of Bombay, because she loves clichés. Trained in Applied Psychology, she has an avid interest in understanding how the world around her works through the lens of culture and aesthetics.

.jpg)