Publishing Discovers The Cinema

29 Aug, 2020 | Archival Reproductions by C Y Gopinath

1978 should go down as the year when publishers began to realize, with the slow, disbelieving smile of a prospector that India’s film audience is inexhaustible. It does not get bored seeing the same faces in film after repetitious film as it does not get bored hearing variations of the same shrill songs. Publishing houses have now discovered what magazine editors knew already; that there is a readership for any writing about the mythic world of films and film stars.

1978 should go down as the year when publishers began to realize, with the slow, disbelieving smile of a prospector that India’s film audience is inexhaustible.

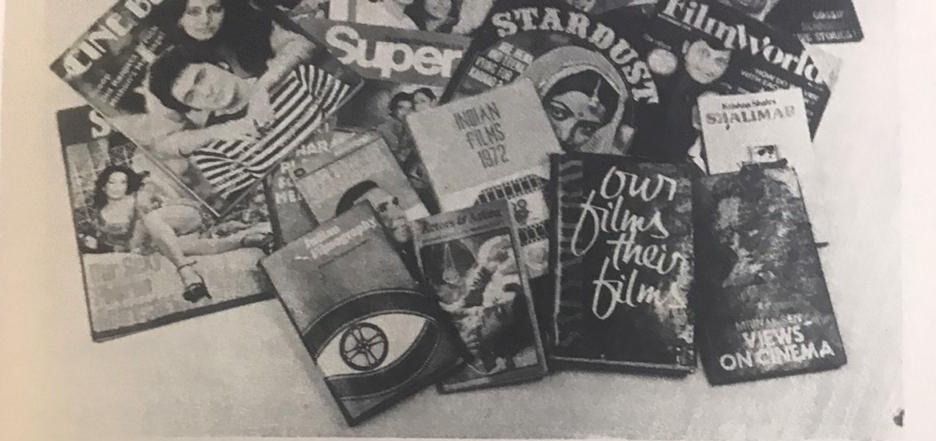

There are over 630 film magazines, 45 in English and the rest in regional Indian languages, and none of them ever fails. But in July this year, Stardust, India’s premier film monthly, acted on a hunch that there was a much wider marker for their magazine. The magazine had been selling between 98,000 and 1 lakh copies per issue in the hands of India Book House, their longtime distributors. Stardust took over its own distribution and set up an in-house agency called Stardust Distributors. Distributors boycotted the magazine. But sales did not drop and in October 1978. Stardust sold 1,18000 copies, not counting its 4,000 subscribers countrywide.

As an executive at Orient Longman puts it: “Booksellers and film-makers are waking up to their mutual interest. They are realizing that it is possible to sell the book through the film and the film through the book.”

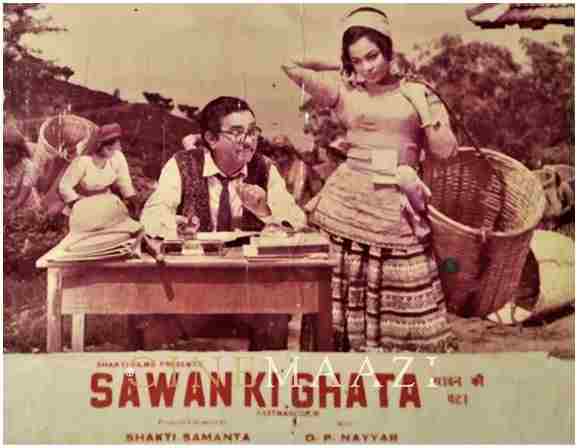

The success of Stardust proved something: that even though more than 45 journals in English alone are competing for readership there is room for them all. Stardust’s closest competitor, Super, two years old and full of life, moved into the breach left at IBH by Stardust’s desertion. Super’s sales rose between July and November, from 50,000 to 75,000 copies per month. To maintain even that level demands ingenuity, because the subject matter is limited. To stay ahead of the rest of them, Stardust and Super have introduced new gimmicks into film journalism. Stardust began a feature in which stars interview each other. Super recently allowed Zeenat Aman to edit an entire issue of the magazine. Stardust, seeing the fog lift to disclose new vistas of readership added 32 pages to an already bulky magazine. The sales figures confirm that these changes are bringing in new readers. A new magazine, Star Monthly, joined the list of film publications last November. The print order for the first issue alone was 20,000 copies. Film writing sprouted a small green shoot this year when Vikas Publications brought out a book titled Actors On Acting, by Mohan Bawa. The book, a collection of rather sketchy interviews with about a dozen Hindi film stars, examines - but only superficially - the methods to which different actors subscribe. Mohan Bawa, a film journalist for many years, is now the first of his profession to be read by the hardcover market, and his book is a maiden attempt at selling ‘filmi’ journalism in book form. There have been other books concerned with stars, such as Vinod Mehta’s excellent biography of Meena Kumari, but actors on acting breaks new ground. It did tolerably well despite its dull fare. Mohan Bawa’s second book, How The Stars Ate A Reporter For Breakfast, with its catchier title, promises more action, and already some excerpts from it have been serialized by Super, a case of cousins helping each other out. The book itself is due for release soon. It’s apparent that book publishers have bought the idea that books on films can ride on the film industry’s shoulders. As an executive at Orient Longman puts it: “Booksellers and film-makers are waking up to their mutual interest. They are realizing that it is possible to sell the book through the film and the film through the book.”The latter is not a new idea. Hind Pocket Books have regularly released novelized versions of films such as 27 Down (by author Ramesh Bakshi), Rajanigandha (Mannu Bhandari), Achanak, Khushboo, Mere Apne and Faraar (all by Gulzar). The book version of K.A. Abbas’s Bobby, released by star publication in 1973 thrived on the film’s popularity. The terrain is a charted one. But not before this year has the idea been packaged so competently that it appears brand new. Krishna Shah’s Shalimar, about which the film-makers themselves said so much that everyone else began talking, establishes a trend. A very high-pressure promotional campaign announced the book version of Shalimar. It was billed as more readable than James Hadley chase, Alistair Maclean, Ian Fleming and a number of other thriller heavyweights. Its author was Manohar Malgonkar, well-known for his novels such as A Bend in the Ganges. The publicity also named a book to follow: one about the making of Shalimar, being written by publicist Bunny Reuben.

The only hollow note here is that the published product does not match the vigour with which it is pushed.

The only hollow note here is that the published product does not match the vigour with which it is pushed. Shalimar the book, does no credit to an author of Malgonkar’s stature, and it is debatable whether the making of the film was so epoch-making as to warrant another book. Still, it seems that books on film are here to stay. Most Indian film-makers fancy their work to be polished gems about which too much cannot be written or said.

Sadly, the ones who avoid such sensational publicity are also the ones who could make powerful contributions to film publishing.

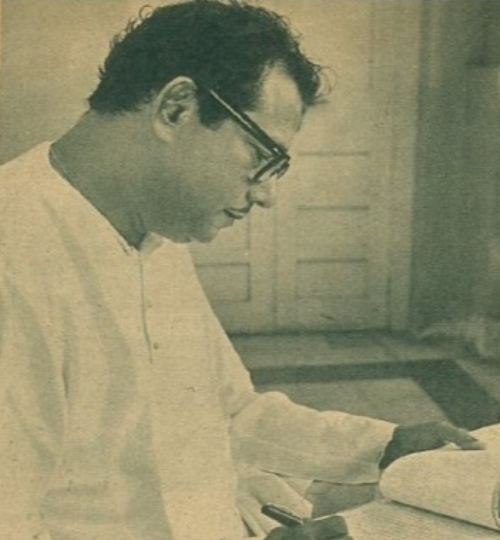

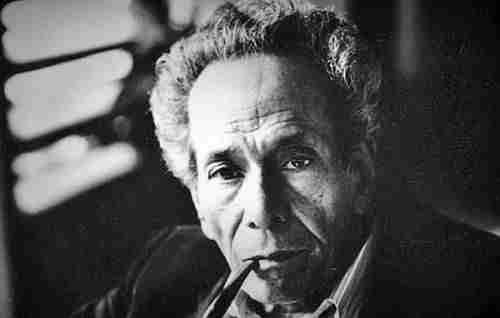

Sadly, the ones who avoid such sensational publicity are also the ones who could make powerful contributions to film publishing. Satyajit Ray’s Our Films, Their Films, published by Orient Longman in a Rs. 60 hardback edition, is the only book on a major Indian film-maker’s views about cinema. The hardback edition was out-and sold out within a month of its release in 1976. The paperback reprint soon followed. Now, in the wake of Ray’s controversial and brilliant Urdu film, Shatranj Ke Khilari, interest in Our Films,Their Films has picked up, and second paperback reprint is due this year. Had Shatranj itself faced fewer problems in its own country, we might have seen another valuable addition to film literature: the screenplay of the film. For the present, that project remains shelved.

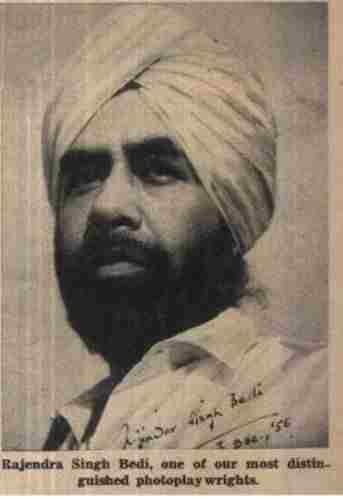

Elsewhere, on a smaller scale, India is seeing published screenplays. Akshara Prakashan in Karnataka has brought out the screenplay of the award winning Ghatashraddha in February 1978, making a first in the Kannada language.

Elsewhere, on a smaller scale, India is seeing published screenplays. Akshara Prakashan in Karnataka has brought out the screenplay of the award winning Ghatashraddha in February 1978, making a first in the Kannada language. The second screenplay, of the film Ondanondu Kaladalli, is awaiting release this year. Orient Longman published the screenplay of Ray’s Seemabaddha in an English translation called Company Limited.But screenplays are not sellers. They cater to an elite, cineaste (rather than cinema loving), professional audience. Despite their content, they are not a match for ‘filmi’ magazines or books based on ‘filmi’ journalism. Aruna Vasudev’s Liberty and Licence In The Indian Cinema - another Vikas book priced at RS. 40 - is described by reviewers as a must for anyone interested in the history of film censorship in India. The book is lucid but its audience is limited.

Two trends have emerged on the film publishing scene in india in 1978. On the one hand there are the few solid books on the film medium and these move slowly in the bookshop. On the other hand there are growing numbers of books and magazines on films, stars, and their activities - and a million people waiting to buy these. The two trends reflect the balance between art and frippery in the Indian cinema.

465 views

Tags

About the Author

.jpg)