1975: Why Was The Year So Good To Hindi Cinema?

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

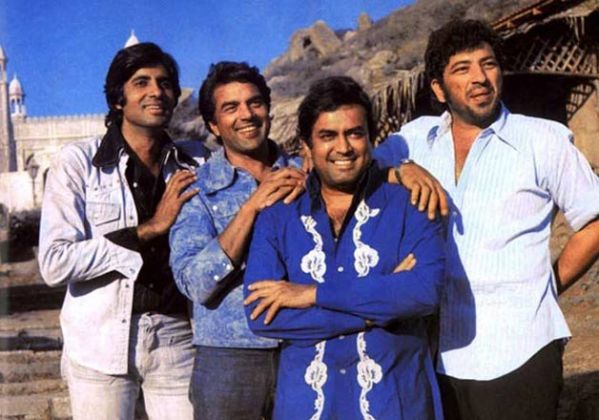

In terms of output and glory, some of it everlasting, it would be an understatement to term the year 1975 as a good one for Hindi cinema. In a way, 1975 was perhaps the first and last time when all variants of Hindi cinema across genres, formats, and styles truly coexisted. While readily recalled as the year when Sholay was released, the year also saw the release of some of Hindi cinema’s most iconic films. Besides Deewaar, the other Amitabh Bachchan-Salim-Javed film of that year apart from Sholay, it was also the year of Julie, Chupke-Chupke, Dharmatma, Aandhi, Mili, Aamanush, Pratigya, Jai Santoshi Maa, Khusboo, Rafoo-Chakkar, Zameer, Warrant, Mausam, Khel Khel Mein and a few more.

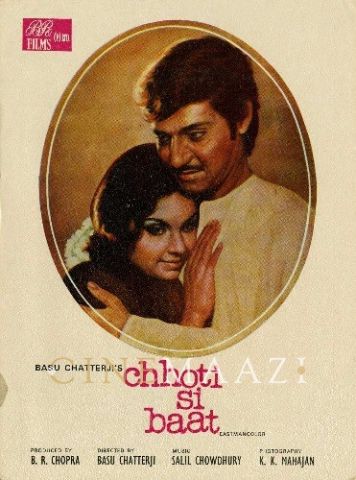

It’s not just that 1975 was good to popular Hindi cinema. In fact, it was also the year in which Shyam Benegal’s Nishant kept up the promise of the filmmaker’s debut film Ankur (1974) and cemented the parallel cinema movement that was initiated the year before. Beyond mainstream and art-house cinema, the year also witnessed the arrival of the middle cinema with Basu Chatterjee’s Chhoti Si Baat establishing Amol Palekar as a new kind of leading man.

While in the ensuing years both middle and parallel cinema went on to get better, popular cinema for some reason couldn’t make much of the brilliant year that 1975 was. Interestingly enough, it might not have been for the want of trying that one saw a downward spiral in the quality of popular Hindi cinema post-1975. To understand why the year 1975 adversely impacted popular Hindi cinema instead of taking it further, one needs to juxtapose the 40th anniversary of some of India’s best-loved films with the 40th anniversary of the country's darkest hour - the Emergency.

Imposed at a time when films took at least a couple of years to be made, the Emergency resulted in a series of diktats on the film fraternity, and like many Indians across professions, filmmakers too didn’t have an option but to tow the official line. Actors, singers and directors were commanded to not only sing praises of the then Congress government, and especially Sanjay Gandhi, seen by many as the architect of the Emergency, but also appear for television specials and other events. Some like Dev Anand, Kishore Kumar, and Shatrughan Sinha were officially banned by the information and broadcasting ministry, but more than anything, the fear psychosis that seeped in when the Emergency was officially announced in June 1975, refused to leave the minds of filmmakers.

As a result, many of them perhaps simply chose not to court any kind of trouble and opted to make safe, entertaining and high on escapism kind of films, something particularly visible in the films released from 1977 onwards. Forget an Aandhi that got banned from being screened on national television as it was rumoured to be based on the life of the then prime minister Indira Gandhi, or even a Deewar, in which moralities are easily traded for riches in the wake of class disparity, films like Chacha Bhatija (1977), Dream Girl (1977) and Hum Kisise Kum Naheen (1977) hardly seem to push the envelope. Even Bachchan and Dharmendra who had films such as Mili and Pratigya besides Sholay and Chupke-Chupke in 1975 were, in a sense, relegated to near-fantastical distractions like Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), Parvarish and Dharam-Veer (1977).

One can see a clear demarcation between popular Hindi cinema before and after 1975, and the films in the first half of the decade were not only inspired by what was happening around, but were also true to the universe they were created in than the ones that were made after Emergency was imposed. On the face of it, there is very little in Deewar’s narrative that suggests the political unrest the country was experiencing in and around 1973 when Salim-Javed were writing the screenplay. But in Nasreen Munni Kabir’s book Talking Films, Javed Akhtar says that it took the duo (Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar) a mere 18 days to write the screenplay of Deewar in one fervent outburst and credit the charged-up environment as the inspiration.

In the year of Sholay and Deewar, most other films would have had to fight for their place in the sun but almost all memorable films of the year stand out for reasons specific to them. The manner in which most box office hits of the year were spread across genres and have managed to hold their own over the last four decades in the face of Sholay, the sole reason why 1975 is enthusiastically recalled, speaks volumes. Even though many of these are today remembered for trivia such as the accidental superhit that practically created a new goddess (Jai Santoshi Maa), or their songs (Julie, Khel Khel Mein, Mausam, Amanush), or the ones that ended up being genre-defining (Chhoti Si Baat, Chupke-Chupke, Nishant), they nonetheless are a testimony of an era when popular Hindi cinema was more than escapist entertainment. Would a majority of popular Hindi cinema not turn the way it eventually did had the Emergency not sounded a silent death knell of sorts? One could argue that this idea probably postulates way too much but what, then, can explain the sheer drop in the quality of commercial cinema towards the second half of the 1970s.

This article was originally published in Daily O on 08th September, 2015. The images used in the feature are not taken from the original article.

Tags

About the Author

Gautam Chintamani is a film historian and the author of Rajneeti (Penguin-Random House, 2019), the first biography of Rajnath Singh. He is the author of the bestselling Dark Star: The Loneliness of Being Rajesh Khanna (HarperCollins,

2014), The Film That Revived Hindi Cinema (HarperCollins, 2016) and Pink- The Inside Story (HarperCollins, 2017).

.jpg)