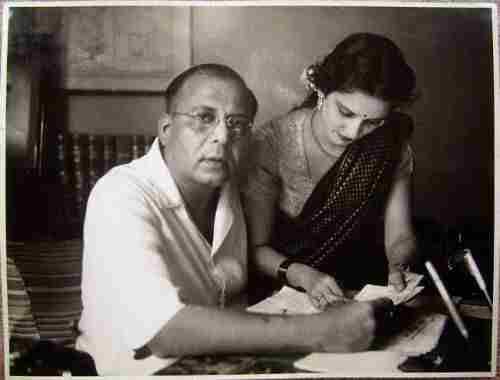

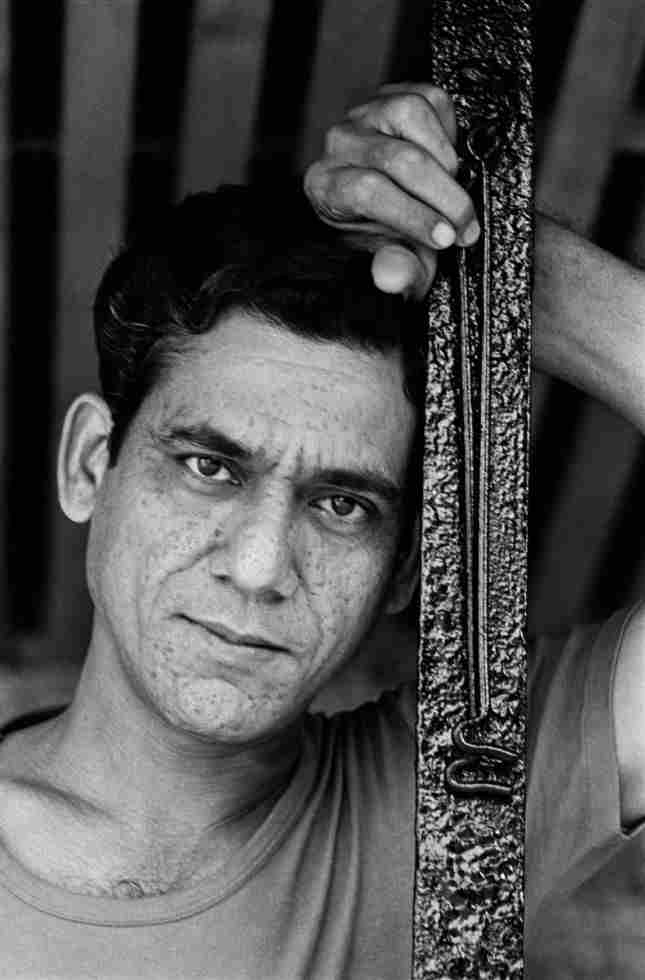

Om Puri – The Luminance of a Natural Actor

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2, and have it saved to your account for one year.

On May 23, 1999 in the ICC World Cup match Sachin Tendulkar scored a majestic 140 coming back after the demise of his father. His innings was an epitome of grace, an inner fight overcoming emotions and reaching out to his lost father. In the same match, another Indian batsman scored a stoic 104 but his heroics paled in comparison to the Little Master. In the very next match three days later against Sri Lanka the same batsman scored 145. This time he was overshadowed by his captain Sourav Ganguly whose humongous 183 was the highest One Day International score by any Indian till that time. Even three years back when both these players made their debut against England in the Second Test, Sourav marched away with all the glory for his princely 131 against the other’s 95. In the Third Test Sourav scored yet another hundred, Tendulkar blitzkrieged with 177 and my little hero scored 84. In both these tests, he batted at number 7 as compared to Sourav at number 3, which to an extent justifies his scoring less runs. In the longer run he marched past his illustrious friend in terms of batting prowess and runs scored though Sourav’s legacy as a cricketer has multiple dimensions to its credit.

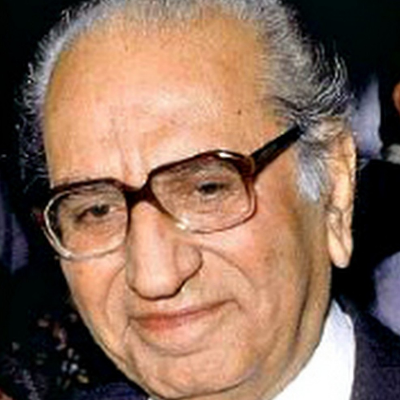

Rahul Dravid to me is that citadel of relentless performance who is never bothered about the fame of others who at their very best can only strive hard to match his level. The Sourav-Rahul friendship and competition, their fierce professional battle to surpass each other resonates in the camaraderie of Naseeruddin Shah and Om Puri – two of India’s finest film actors of all times. Naseer, like Sourav is the more flamboyant of the two and is undoubtedly the more influential and the more glamorous.

In their initial journey into the film world in the early 70s, it was Naseer who would get the meaty roles and Om though brilliant, had to remain content with cameos. At times it was tragic considering the amount of power Om could bring in into his performance. Sparsh (1979) for example is a film that got Naseer his first National Award and yet Om stood his ground in the few scenes he could get to show his talent. Both Naseer and Om along with Smita Patil and Shabana Azmi would embark upon a journey hitherto unexplored in Indian cinema, leave alone Hindi cinema only. Their films for the first time had the authentic rural touch, the brush of the underprivileged, lower-class representation which didn’t exist before that time. It had always been middle-class directors using actors with Brahminic features – from Ray to Ghatak, from Bimal Roy to Shantaram and others.

A number of actors with lesser looks have gone on record saying that by watching Om and Naseer (more of Om because of his ‘unconventional’ looks) they got the courage to become film actors. Irrfan Khan, Nawazuddin, Manoj Bajpai and a few more can be considered to be the direct descendants of Naseer and Om in a sense. However, not only the later actors but also a number of directors could think of subjects of their choice which they wouldn’t have dared if there were no Naseer or Om. Who can forget Mrinal Sen’s path-breaking Genesis (1986) which would never have been possible without this iconic duo.

The rustic vigour which they can bring into their acting has no precedence in Indian cinema. Their complete unawareness of their physical self could take them to heights difficult for other actors to scale. Even today!

With Govind Nihalani’s Aakrosh in 1980 Om Puri probably got a role where he could get substantial screen time. One of the all-time classics, the film deals with the exploitation of the under-privileged and the farcical Indian judiciary system. It is one of the several films of the late-70s and 80s where the directors would take up social oppression as their subject which seems logical and justified considering the memories of rage and state vandalism inflicted during the Naxalite movement less than a decade back. Om Puri didn’t have enough dialogues to speak but his vacant stare transforms into a violent rage that chronicles the helplessness of the down-trodden in the Indian society.

If his deep yet distinct voice is one signature attribute, Om Puri’s eyes, apart from everything else, will be the first physical attribute of the actor to be noticed. He have used them as a reservoir of angst – sometimes subdued and meek as in Aakrosh, Chokh and Arohan (1983) or in evocative anger as in Ardh Satya (1983) or even the 1987 Television Film Tamas by Govind Nihalani. The power latent in them was without doubt a hallmark of the intensity of his early portrayals.

Even in Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982), Om Puri’s first venture in an international project, his poignant minuscule role is significant and etched in the minds of all who have witnessed the spectacle that bestowed Gandhi with God-like qualities! But that is a different debate altogether. What intrigues me is the power of Om Puri’s delivery and the subtle acting of his eyes that turn from defiance to submission.

Starting from 1976 with his first film Ghashiram Kotwal if we look at the trajectory of Om Puri’s career we can probably divide it into two phases – the first being from 1976 till 1992 and the last being the next two decades or slightly over. During the first phase, he along with Naseer prospered most as an actor ably complementing the emergence of the New Wave Indian ‘parallel’, ‘art-house’ cinema.

Aakrosh in 1980 first made him noticed outside of Naseer’s shadows and the circle got complete with Arohan in 1983 for which he received his first National award for Best Actor. However the film that transcended Om Puri from an actor who could play only the rural, down-trodden, ‘dehati’ roles to one who could take up a urban dashing one as well was Ardh Satya by Govind Nihalani in 1983. Om Puri played the police officer Anant Velankar with unbelievable stoic roughness that grabbed him the second National Award for Best Actor in three years.

Yet in another scene he can be a hesitant and shy romantic in his own way, flustered by the presence of a diminutive Smita Patil and reading out a poem by my dear friend Dilip Chitre.

The very next year Om Puri stunned everyone with a comedy performance in Jaane Bhi Do Yaron (1983) which in my book is probably one of the best satires this country ever produced. In a cast that is star-studded Om as a swanky, aggressive, abrasive businessman acted with gaiety and would sport a dark sunglass throughout the film to mask his expressive eyes. If there was a slight doubt in anyone’s mind that he was over dependent on one physical attribute of his in his portrayals he completely banished that point of view.

During this first phase Om Puri, unlike Naseer started appearing on Television more often including Tamas , Bharat Ek Khoj and Kakaji Kahin, the last being a political satire. He also acted in the British Television Series The Jewel in the Crown in 1984. Apart from several other significant performances the one film that deserves special mention during this first phase is Narsimha (1991) – an out and out Hindi mainstream commercial film where he played a villain. In this film, like Jaane Bhi Do Yaron, he sported the dark sunglasses and yet the dreadfulness of his ruthless villainy was portrayed with clinical perfection conforming to the demands of mainstream cinema.

In 1992 Om Puri starred as Hazari Pal, a rickshaw-puller of Calcutta in Roland Joffe’s Hollywood endeavour City of Joy. This is Om’s first international project and also one of the initial ones for any Indian actor for all time.

Side by side he ventured regularly in mainstream Hindi films including and as diverse as Drohkaal (1994), Maachis (1996), Chachi 420 (1997), Aastha, Maqbool (2003), Delhi-6 (2009), Hera Pheri (2000), Dabang (2010) and Bajrangi Bhaijaan (2015) to name a few. Most of these films didn’t offer him significant roles and most commonly transformed him into a laughable parody of comic characters or at most insipid villains. It was the International films which during this second phase provided him with an international fame and reputation and elevated him from being just a tragic figure like Karna as opposed to Naseer’s Arjuna! It was probably Om Puri’s conscious decision to change shores to make his mark as an international actor, to be known widely in Britain as well as Hollywood. In doing this he in a sense could redeem some of the lost pride in playing second fiddle to Naseer in the first phase of his career.

On a personal note I had the privilege of speaking to him only once over telephone. I was then writing a book on Soumitra Chatterjee who is the other legend of Indian cinema and a senior to both Naseer and Om by over a decade. I wanted to have their comments on Soumitra and sent them two handwritten letters just in case they agree for interviews. After a couple of months on a lazy Sunday morning I spoke to Om Puri, he called up and wanted to give his views on an actor who, he said, was a very ‘special’ one – “Soumitra-da is a very natural actor. He is one of the finest around and not only in Indian cinema but in world cinema as well, you will not find many like him…He is so smooth, so free the highest acumen of an actor where you can make out that the actor’s craft is not premeditated. And his range is so vast! It is so unfortunate that he didn’t do any Hindi films. Our general audience is not yet ready to watch films with subtitles otherwise his films could have been released in theatres. I think that it is one of the biggest misfortunes that the general Indian audience could not get a chance to watch his films and he remained largely a Bengali actor. I have never got the opportunity to act in any film with him but I have the highest regards for him as an actor.” I was touched by Om Puri’s gesture of calling up on his own and his assuring me that I can call him any time to discuss further. I didn’t though, and never ever after that half hour’s conversation although I promised him to call back once the book is out.

He remains to me a special person, an actor who finds a place in the highest echelons. In the ultimate analysis, he is neither a tragic Karna nor a less-regarded Rahul Dravid. He is at his helm, one of the brightest stars of the Indian cinema sky. He will glow with his natural luminance, and no one can ever cast a shadow on his magical abilities. In his humble elocution of life, he is a hero of the common man; he is our very own Om Puri.

This article was originally published in Silhouette magazine on 8 January, 2017. The images used in the feature are not part of the original article and is taken from the internet.

Tags

About the Author

Amitava Nag is an independent film critic and editor of film magazine 'Silhouette' (www.silhouette-magazine.com) since 2001. Till date Amitava has authored 5 books on cinema including 'Satyajit Ray's Heroes and Heroines', '16 Frames' and 'Beyond Apu: 20 Favourite Films of Soumitra Chatterjee'. Amitava also writes poems and short fiction in Bengali and English and authored a collection of short stories each in English and Bengali, and an anthology of Bengali poems.His first anthology of English verses and a selected translation of Soumitra Chatterjee's poems are awaiting publication.

.jpg)