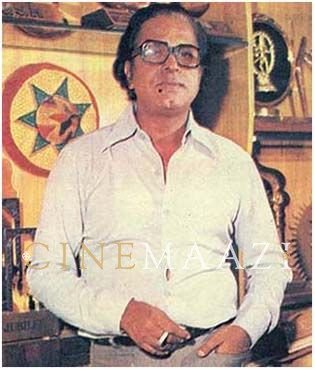

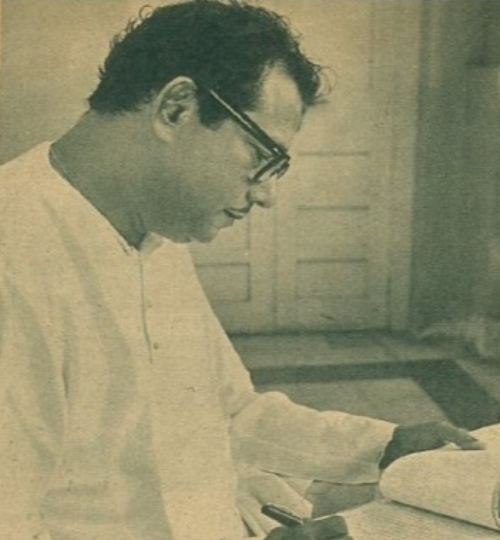

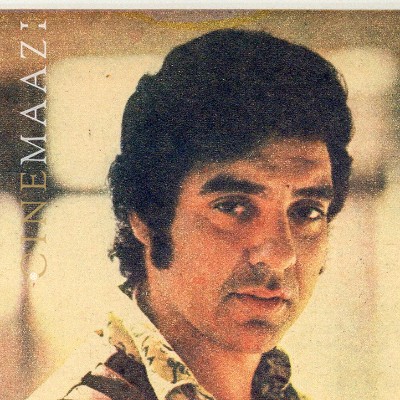

Mani Kaul

Subscribe to read full article

This section is for paid subscribers only. Our subscription is only $37/- for one full year.

You get unlimited access to all paid section and features on the website with this subscription.

Not ready for a full subscription?

You can access this article for $2 , and have it saved to your account for one year.

- Born: 25th December, 1942 (Jodhpur, Rajasthan)

- Died: 6th July, 2011 (Gurgaon)

- Primary Cinema: Hindi

While parallel cinema stalwarts like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani and Mrinal Sen would forever be applauded for turning the camera towards the complex issues of marginalised subjects of society, none challenged the very notion of what a film is like Mani Kaul did. Over the course of a career spanning three decades, Kaul persistently brought into question the linear narrative form that had been practiced in both commercial and art cinema. He would advocate that challenging commercial cinema did not just translate into finding new content, but completely reinventing the bourgeois cinematic form itself. His films have been deemed notoriously difficult and unfathomable, been accused of alienating the very audience it sought to address and being outrageously cavalier of the commercial demands of the film industry.

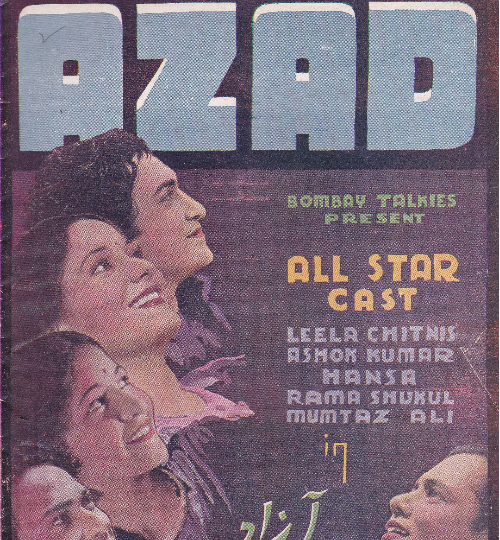

Born on 25 December, 1942 in Jodhpur, Rajasthan in a Kashmiri Pandit family, Kaul was an avid film watcher since his childhood days. He would spend his days watching films free of cost at a theatre owned by a classmate’s family. He even went to the extent of stealing Richard Arnheim’s Film as Art from the local library of the city. Though he grew up steeped in commercial fare, it would be his first viewing of a documentary that transformed his notions of cinema. He would graduate from the University of Jaipur in 1963 and later join the Film and Television Institute of India where he would come under the aegis of Ritwik Ghatak. He would act in many students’ films during his tenure there, and would also make an appearance in another landmark parallel cinema film, Basu Chatterjee’s Sara Akash(1969). He made several short films and documentaries before his seminal feature film debut – Uski Roti (1969). Widely credited as one of the films that sparked off the Indian New Wave (as well as the Film Finance Corporation’s first significant forays into direct film production), its non-linear treatment and often abstract visuals stood in stark contrast to what had been accepted as realist cinema thus far. According to Shyam Benegal, it was a landmark film on par with Pather Panchali (1955). Its languid pace and tendency to flout traditional acting and visual norms earned it as much critical flak as acclaim though. The film ended up winning the Filmfare Award for Best Film (Critics) and won K K Mahajan a National Award for Best Cinematography. It would also be Kaul’s first adaptation of the modernist Hindi writer Mohan Rakesh’s works.

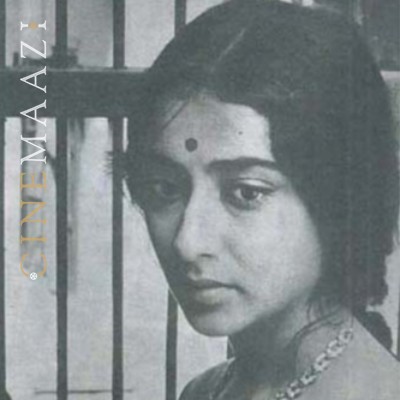

His second film Ashad Ka Ek Din (1971) was adapted from Mohan Rakesh’s play and featured the poet Kalidasa as one of its main characters. The characters’monologues were pre-recorded and played back during shooting, in order to free the actors from following traditional acting conventions. The result is a film even more contemplatively paced than Uski Roti with the slow panning camera complementing the surreal ambience. It would win Kaul his second Filmfare Award for Best Film (Critics).

Duvidha (1974) would adapt a Rajasthani folk tale and would be partly financed by a co-operative set up by the painter Akbar Padamsee. Inspired heavily by Kangra and Basohli miniature paintings, Kaul designed the mis-en-scene to highlight the various intensities of everyday rural life while simultaneously emphasising the stifling patriarchal atmosphere of an orthodox society. The film received a great deal of attention when it was screened in Europe but was subjected to a ferocious critique from Satyajit Ray who decried the New Wave’s experimental and obscurantist strategies.

He was a recipient of the Jawaharlal Nehru Fellowship from 1974-76. He would also be a part of the Yukt Co-operative who made Ghashiram Kotwal (1976). When the Films Division wanted him to remove a shot from the Emergency era documentary Historical Sketch of Indian Women (1975) he refused.

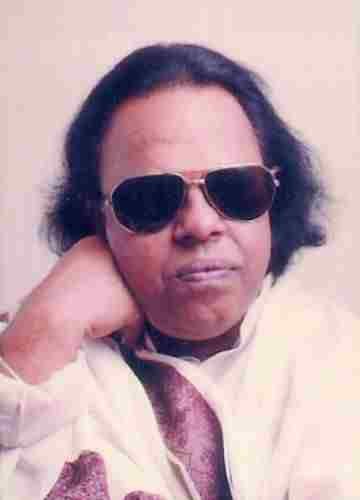

Kaul was inspired by the form of classical music such as dhrupad and wished to translate it in cinematic terms. For him, there was no direct relation between seeing an object and its meaning, just as there is no explicit meaning in classical music. He himself studied dhrupad under Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar and studied Anandvardhan’sDhanwaloka, a 9th century Sanskrit text. These ideas informed his film Satah Se Uthata Aadmi (1980) which was based on the works of G M Muktibodh. Featuring a camera that was constantly in motion and dialogues heavily featuring internal monologues, Kaul’s minimalist treatment removes the film from its literal dimensions to an abstract one, in which the viewer is confronted with the subjectivity of the text rather than mere characters. He would explore the dhrupad form in depth in his 1982 documentary Dhrupad which featured Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar and Fariduddin Dagar. The film was remarkable for its innovative camerawork, as evocative as the music it featured.

He would primarily make documentaries through the 80s before returning to feature films with an adaptation of Dostoevsky in Nazar (1989), featuring Shekhar Kapur and Surekha Sikri. Kaul’s ability to bring out the unexpected within the film’s claustrophobic spaces was commendable. He would adapt Dostoevsky again with Idiot(1991) which featured a young Shah Rukh Khan. It was screened at the New York Film Festival and released as a four-part miniseries on Doordarshan called Ahamaq. His other films include The Cloud Door (1994), Naukar Ki Kameez (1999), Ik Ben Geen Ander (2002) and A Monkey’s Raincoat (2005). He also made several documentaries including nine acclaimed ones for the Films Division. He produced Gurvinder Singh’s award-winning film Anhey Ghorey Da Daan (2011).

Perhaps the chief difficulty of watching a Mani Kaul film was the primacy he gave to time instead of space in his films. For him, cinema was not about controlling or regulating a space, but a more introspective medium, which frees both the camera and the viewer from following a narrative. Inspired equally by folk and classical music, the paintings of Henri Matisse and the austere films of Robert Bresson and Yasuziro Ozu, he would develop an elaborate theory of aesthetics of his own, later published in the book Concepts of Space: Ancient and Modern. Kaul was obsessed with the act of seeing things all his life, and he wished his films to be an introspection on how we see things, and not just what is seen. Though his films never found much acceptance among audiences in his lifetime, they remain hugely influential on independent filmmakers till date. The visionary filmmaker passed away on 6 July, 2011 in Gurgaon.

-

Filmography (8)

SortRole

-

A Monkey’s Raincoat 2005

-

Naukar Ki Kameez 1999

-

Idiot 1991

-

Nazar 1989

-

Dhrupad 1983

-

Duvidha 1973

-

Awards (2)

National Film Awards, 1974

Best Film: Duvidha (1973)

Filmfare Awards, 1974

Critic's Award for Best Film: Duvidha (1973)

.jpg)