Somnath Kundu: Making up the Stars – A Star Among Make-up Artists

In recent years, Somnath Kundu has managed to bring the contribution of the make-up artist to the forefront with his work in Chander Pahar, Ek Je Chhilo Raja, Gumnaami and other blockbusters. In a freewheeling conversation with Cinemaazi editor Shantanu Ray Chaudhuri, he talks about his father and grandfather – pioneering costume designers who worked with stalwarts like Debaki Bose, Bibhuti Laha, Tapan Sinha – and his own journey in films…

Tell us something about your childhood days – your father and grandfather were both well-known costume designers.

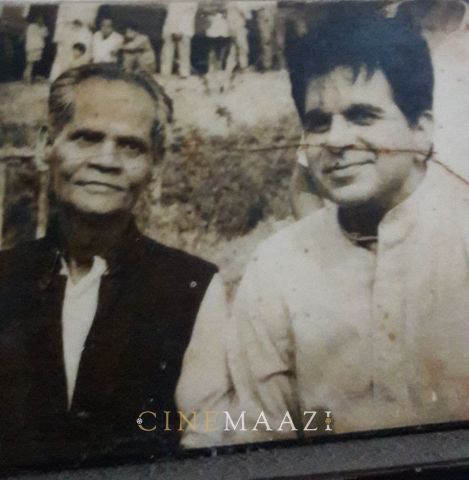

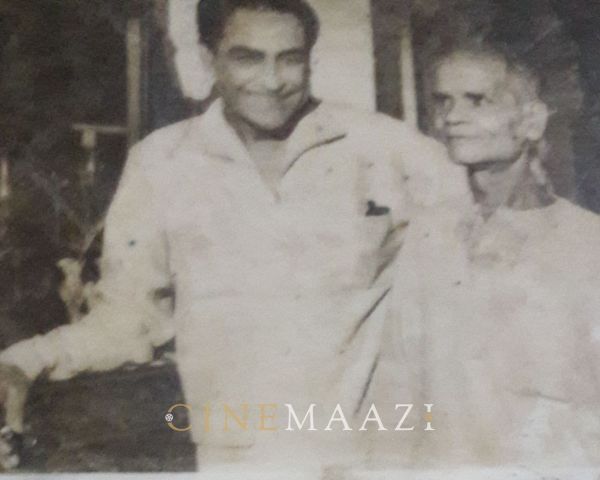

My earliest memories go back to the time I was five or six years old. Not that I really understood what it was that my father, Shyam Kundu, did. My dadu (grandfather) Ishwar Jyotindralal died well before I was born on 15 November 1976. Baba used to talk of him with a lot of pride. Dadu was an artist of the highest order. He designed the costumes of classics like Morutirtha Hinglaj, Haate Bajare, Sagina, Golpo Holeo Shotti, Jhinder Bondi¸ Rajdrohi¸ Apanjan, Dewa Newa, Jatugriha and many others. Nowadays when a lot of the old fashions make a comeback in cinema, I realize how it was Dadu who actually created the designs. He was a regular collaborator with Tapan Sinha – who began as a sound engineer and then became a director. It was while working on the Hindi version of Tapan Sinha’s Sagina that Dadu had a heart attack in Bombay. Dilip Kumar got him admitted to Lilavati Hosipital, before he returned to Kolkata where he passed away.

Baba was also an exceptional painter. He was also an expert at making models – and entirely self-taught at that. As a young boy, he won the second prize from Anandabazar for a watercolour. He passed away in 2016. I remember him as extremely hard-working. After Dadu passed away, he single-handedly managed the family – looking after his siblings too. It was Baba who inspired me to become a make-up artist. He believed I could make a name for myself as one.

But it was thrilling to see Baba’s name in the credits when we went to see the films. Baba took the family – ma, my two elder sisters – to watch films like Kiranmala, and I remember shouting, ‘Look, Ma, there’s Baba’s name.’ Baba too used to point out Dadu’s name when his films were shown on TV. Life has come a full circle. Now, when my films are screened on TV, my son screams at the top of his voice: ‘Look, look, Baba’s name!’ I feel so proud.

Did you accompany your father to the sets of his films?

Baba took me to the sets with him two-three times. Once, for an audition as a child artist in a film by Tarun Majumdar. I don’t remember the name of the film. It needed child actors to play characters working as pavement teashop boys, shoeshine boys … basically poor, needy children. Baba took me along. Tanu-jethu asked me my name and then told me to stand next to an almirah in the room. They wanted to measure my height. By then, I had impressed Tanu-jethu with my constant chatter – I was a very talkative boy. Eventually, I could not do the role as I was a little too healthy for the requirement of the character. They needed boys who looked impoverished. It was at Tanu-jethu’s shoot that I saw Tapas-da (Tapas Pal) for the first time. What a handsome face, curly-haired, the very picture of Lord Krishna. He asked me my name, patted my cheek. Little did I know that I would work on his make-up one day.

I also visited Technicians Studio and New Theatre Studio (known as NT 1). Before entering NT 1, Baba asked me to pay my respects at the gate. I did not understand why. He said that my grandfather had worked there. It had been the karmabhoomi of many stalwarts. At that time I did what my father said without really understanding the importance of the place. It was only later I realized that those studios are as good as temples for people like us. I only hope that future generations of technicians regard them with as much respect.

Did your father have work on a regular basis?

Things were difficult … when Baba had work, he would be engaged a couple of months before the shoot began and for the duration the shooting lasted. Then, all of a sudden, he would have no work in hand as shooting for a film had ended and another was yet to begin. Technicians like my father had a tough time. I used to ask Maa why Baba did not go out on work. She explained that Baba did not have work at the moment as Tapan Sinha or Tarun Majumdar were in-between films. Ma used to instruct us not to make any demands of Baba … don’t waste paper in your notebooks, eat whatever was on offer. There were many such lessons in economy. It was later that I came to know that when there was no film work, Baba used to make ends meet through stitching and tailoring assignments. Maa used to help him out sewing the hem of blouses, stitching buttons. Yet, they never shirked their responsibility when it came to educating us. They never let us realize how bad the situation was financially.

Tell us something about your education. What did you want to be when you grew up?

I was a mediocre student. All of us siblings studied in Bengali-medium schools. Baba did not have the means to afford English-medium schools for us. I studied at the Chittaranjan Colony Hindu Vidyapith in Baguiati. I had heard that legendary actor Ajitesh Bandopadhyay used to be a teacher at the school. Though never brilliant in academics, I managed to get through my classes every year. After passing school in 1994 – I missed first class by a mere seventeen marks, though I scored letter marks in physical education – I enrolled in City College with Bangla honours. I graduated with 55 per cent marks.

I was very keen on a career in education. I loved it and had a flair for teaching. I used to give tuitions from my high-school days. I met all my educational expenses on my own after a point. I did not want to pressure Baba for anything. By that time, Baba was keeping unwell after a heart condition in 1993. I conducted tuition batches of four-five students every morning. There were also a couple of students who took home tuitions.

It was while graduating, sometime in 1996, that I got an opportunity in the film industry. Baba wanted me to be make-up artist. He knew I had a knack for drawing. Maybe I had inherited it from him. I never took any lessons in art – frankly, we never had the means. Like Baba, I was entirely self-taught. It was from him that I learned to make idols. Baba kept insisting that I could use my drawing skills to make a career as a make-up artist – after all, a person’s face is no less than a canvas! I was not entirely convinced. I knew how the industry functioned – half the time one had little or no work. I wanted to be a teacher. That’s why I was continuing with my education against all odds.

The first opportunity came in 1996 – in three films simultaneously. It would keep me employed for six months, but there was a catch. There would be no pay. It was like an unpaid internship as an associate to a senior. At the time, I used to conduct tuitions till 10 a.m., then off to college. After college, I made my way to the studios at 2 p.m. This is how it all began.

How did a career in cinema and as a make-up artist happen?

When my senior Subrata Sinha first gave me an opportunity on my second or third day, unit members liked the work I did. That inspired me, stoked my belief that maybe I could be good at this. It was not as if I watched a lot of films during my adolescence or youth – frankly, I had little time given our conditions – but looking back I realize that I was aware of aspects pertaining to make-up from childhood. I used to accompany Baba to neighbourhood jatras and plays, help him with the make-up, for example, putting on beard and moustache on artists, painting faces … though I never imagined this as a profession at the time, it was something I enjoyed doing.

I took a bus from college to Tollygunge. The man at the gate, Pradyut-da, let me in when I mentioned my father’s name. He asked me to go to make-up room number 10 and ask about the person I wanted to meet. At room number 10, I told the man who opened the door (let’s call him Mr X – I would not like to name him here) that my father, Shyam Kundu, had asked me to meet this person. Mr X told me that the concerned person was at Technicians Studio. I walked over to the studio. At that time, Bengal’s first mega-serial Janani was being shot there. I actually met the person whose elder brother Baba had sent me to meet. He told me that his brother was working at NT1. I made my way back to NT1 and met Mr X again, who now said that the man I wanted to meet was probably working at Indrapuri. Needless to say, I went over to Indrapuri. The place was deserted. So, I made my way back to NT1 and met Mr X again. It was now that he laughed and told me that he was the man Baba had sent me to meet. He mentioned he was testing my interest and patience! He also informed me that he had no assignments in hand as there were no shoots happening.

On my way out, when I informed Pradyut-da, he took me to floor number 4, where a serial was being shot. I observed the work for a while and went back home. Sometime later, I managed to contact Subrata Sinha, who became my guru.

Do you remember your first meeting with Subrata Sinha?

I met him first at Indrapuri Studio on the sets of Rituparno Ghosh’s serial 52 Episode. Of course, at the time I had no idea of how great an artist Rituparno Ghosh was. Subrata Sinha was doing the make-up for June Malia and Gargi Chatterjee. It wasn’t the most auspicious of beginnings. He asked me to hand over a brush and I dropped it. He only said: ‘Somnath, you can’t afford to be tense when working in make-up. And you cannot rush things.’ That was my first lesson in make-up – the need to keep a cool head and focus.

That’s how it all began. I realized that working in the industry was a tightrope work. It entailed unimaginable toil. One could make friends here, but before that came a whole lot of ordeals.

At the same shoot, another senior actor asked me to press his legs. My senior in the make-up department suggested I do as told – it was a part of the work. Baba had told me otherwise – just focus on your work and do not engage in anything out of the scope of your work. I wondered where I had come to. Slowly, things eased out and I realized that like all places, the industry too had all kinds of people. I resolved that in a few months I would do the make-up on the actor who had misbehaved with me on the sets of Bhalobasha. And I did it. Eventually, it so happened that he would let no one but me do his make-up. These are the kind of experiences that make the journey worthwhile.

I worked with Subrata-da for 2-3 years, of which about a year was as an apprentice. Then he took me on as his main assistant. In time, I became so good at it that if he had two films on the floor simultaneously, Subrata-da would leave one entirely to me. I began to visualize a day when I would become an independent artist – no longer as an assistant. There are some many things one can do independently, ideas one can implement, that are not possible as an assistant where you have to follow instructions.

How did your first independent assignment come about?

Around end 1999, I remember being on an outdoor shoot of Sujit Guha’s Prem Pratigya. It had a huge star cast – Sandhya Roy, Rituparna, Prosenjit Chatterjee, Chiranjeet Chatterjee, Tapas Pal. Though Prosenjit Chatterjee had a personal attendant, I was in charge of everyone else. I was feeling a trifle overwhelmed and hence asked Subrata-da: ‘Can we take on another assistant – there are so many stars to handle, and actors like Sandhya Roy need a lot of attention and time.’ I wasn’t sure what the reason was but he shot back: ‘I don’t want you on my next film any more.’ I was taken aback. He must have been under pressure but I was extremely hurt. I rationalized that he must have had his reasons. That is when I started telling people around me that I wanted to branch out independently.

It was in 2000 that I got my first independent assignment. And I am grateful to production controller Pritam Chaudhuri, or Lalu-da, for the same. No other production controller had heeded my request till then. They kept telling me that I had been around barely 3-4 years – there were people who had been assisting for close to 10-15 years and were yet to make the grade. Ranjit Tarani (he was Indrani Halder’s driver at the time and later assisted me in make-up) introduced me to Lalu-da. In fact, when Indrani-di moved to Bombay, Ranjit came to me, saying he had heard that I wanted to go independent and he would like to assist me. When I told him that I was yet to receive my card as key make-up artist, he arranged for a meeting with Lalu-da.

After Prem Pratigya wrapped up, I kept visiting the studio despite having no work. One day, at NT1, I came upon director Ratan Adhikari (he was making Apon Holo Por at the time), Lalu-da and Prosenjit Chatterjee engrossed in a conversation. Seeing me hovering around, Lalu-da called me and asked, ‘Somnath, weren’t you looking for independent work? There’s a film about to start rolling … will be able to do it?’ Of course I said yes. Lalu-da introduced me to Ratan Adhikari, mentioning my work with Subrata-da on a number of productions. Bumba-da too endorsed my work: ‘I know him well – he is very sincere.’ The person who was supposed to be the make-up artist had not turned up – I happened to be at the right place at the right time. Lalu-da told the director that he had made up his mind to given me a break.

The film was Jamaibabu Jindabad, starring Bumba-da and Rituparna Sengupta. My first film as chief make-up artist. It was also the first independent production of Surinder Films and became a big hit when it released in 2000. But for the generosity of Lalu-da and Bumba-da, I would never have had the break I got with Jamaibabu Jindabad. Ratan-da too – unfortunately, he is no more.

Any special memories around Jamaibabu Jindabad?

I was very tense right through, working independently with such big stars. In fact, soon after an outdoor schedule of the film, whispers went around in the make-up fraternity that the stars weren’t happy with ‘Somnath’s work’. However, during the shoot all the actors had praised my work. Ritu-di wanted to hire me as her personal make-up man. I couldn’t accept the offer as I had the responsibility of the whole unit – also, there was so much more to learn, so many others to work with. I spoke to the director and Lalu-da. Would they like to engage someone else? Lalu-da would have none of it – he said that I had done exemplary work and advised me not to pay heed to such rumours. ‘You will complete this film, let anyone say anything,’ he insisted.

One has to be ready for any contingencies at a shoot. In the same film, we had a problem with Kaushik Banerjee’s wig which was not fitting him. The shoot could not be cancelled. I worked on that and saved the day – no one could make out the difference between the wigs in different shots. This being my first film, I feel proud that I could address these issues that came out of the blue. I remember everything about the shoot – there were people who stood by me right through, there were others who weren’t as helpful. Given the difficulties I faced, I decided that I would never hold back in helping any newcomer to the industry. That has been one of the principles I have adhered to all these years – having been an assistant, I am always aware of the lack of confidence and other issues assistants face.

As a light-hearted aside, it was during this shoot that someone in the dance group fell in love with me – she even proposed. But I had just started out. I could not think of anything but my work. And how to help my family out of the financial distress we were experiencing. I literally did not have the time or space to fall in love!

Did you get work on a regular basis after this?

It has been by no means an easy journey. After Jamaibabu, I had no work for six months. By the grace of God, however, I have never had to ask for work after Jamaibabu – even if it took time, work came on its own, based on the goodwill I managed to generate with my work. Then came another film Rakhe Hori Mare Ke. Then Subhadra Chowdhury’s Prahar, which won a National Award. Work was never regular – but one went beyond the call of duty when one had work, attending to the set, trying to engage my assistants, inspire them, working on my own techniques.

You are entirely self-taught – how did you build up on your expertise?

Though I had learned the basics with my guru, Subrata-da, the one film that shook me was Kamal Haasan’s Chachi 420. It was nothing like what I had seen before. It made me feel that there was so much that could be done. I had started reading books on make-up, but after Chachi 420 it became a passion. There was so much to learn about changing techniques, innovations, the use of material as per changing weather. By the time I started working, the era of black and white films was over. However, many of our teachers, the older technicians were still influenced by the techniques used for black and white film, and that is what the younger lot was taught. Thus, there were instances when the colour went awry – faces became too red at times or too pale – you could make out that make-up has been applied. Like editing, the test of make-up lies in no one being able to tell it.

Tell us something about the changes you have been part of in the make-up scene over the years – who were the stalwarts and films that influenced you?

There have been many changes in film technology that have impacted make-up in the last couple of decades. When I started out, most films were shot on Super 16 camera. Then came 35mm camera. Or they used to shoot on 16 mm and blow up to 35. Then 2C, Arriflex. The change from film to digital happened in my lifetime. All of these affected the way we approached make-up. Then there was the film – Fuji had its own tonal quality, Eastman had its peculiarities as did Kodak. We had to be mindful of the film being used. Now, with digital, things have become a little easier. Also, now there’s the monitor which enables the film-maker to see what is being shot and correct mistakes as we go along. When I started working – or before me – we did not have this luxury. We had to be constantly watchful of every aspect on the set. The director and DOP had to take the call based on pure instinct. Nowadays, the monitor enables us to rectify errors while shooting.

Also, earlier we never had the luxury of 3-4 assistants. The sole attendant had to carry the tray, the ice can, be aware of every item in the make-up kit. The make-up artist seldom allowed his assistants actual work on the actors. Assistants had to be at hand to address any needs of the boss or the actors, manage the floor. That changed with the new generation of make-up people entering the fray. It also fuelled the desire among assistants to take this up as a profession because they saw potential to learn and grow – and not remain an assistant for years and years like it used to be. Over the last few years, there has been a lot of work on prosthetics in the Bengali industry – directors and make-up people are investing time and money in this and we no longer have to get experts from Mumbai.

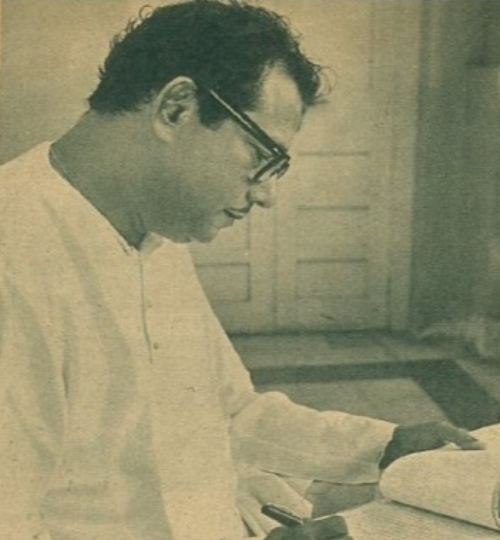

Our work stands on the shoulders of giants who came before us. The way they worked with limited means at their disposal and against technological odds … Consider Ananta Das’s (he was a regular on Satyajit Ray’s films) work in Mrinal Sen’s Akaler Sandhane or Debi Haldar in Mrigaya – the effects they managed in those days was extraordinary. Sailen Ganguly (Bicharak, Uttar Falguni, Deya Neya), who taught at Rabindra Bharati University, was another great name. Of course, he passed away much before I came to the industry. Nitai Sarkar did some great work with Uttam Kumar in films like Agnishwar and Sabyasachi. Bashir Ahmed, Uttam Kumar’s regular make-up artist, was another big name. Debi-da, Debi Haldar, was among the finest I saw at work. He was always reluctant to let anyone remain in the vicinity when he was at work – he used to keep the doors shut. But he loved me and when I mentioned I wanted to watch him at work, he allowed me – he used to call me ‘Kundu’ – ‘Come over, whenever you want to, Kundu,’ he would tell me. He was so innovative and made such good use of the limited resources he had. He worked in a number of Assamese films. He was a regular on Buddhadev Dasgupta’s films (Charachar, Lal Darja, Dooratwa, Neem Annapurna).

People often made fun of me – ‘Somnath is trying to do a Spielberg film make-up here,’ they would say. My argument was – what’s the harm in being prepared? When we finally get the technology and the resources, we can hit the ground running if we are prepared.

Which film do you think gave you a distinct identity as a make-up artist?

In the last twenty years I must have worked in over eighty films. I have already mentioned the national Award-winning Prahar – which had a lot of scope for make-up, including creating one for Rajatava Dutta disfigured in a bomb blast. Goutam Ghose appreciated the work, though at that time few people understood the importance of make-up as an integral part of films. There was Prabhat Ray’s Subhodrishti. Sathihara offered me a lot of scope. But it was Kamaleshwar Mukherjee’s Chander Pahar in 2013-14 that brought me into the limelight. Deb’s last look in the film and a few minor prosthetic work convinced people that I could go out of the comfort zone and take risks. That was the first time my name was mentioned in newspapers talking about a film.

What have been your toughest assignments? Which has been the most satisfying experience?

Ek Je Chhilo Raja raised the bar. Everything after that comes with a lot of expectations. However, make-up is not independent of the film. Once has to follow the director’s vision and what the script requires. There have been many interesting assignments after EJCR. Srijit-da, Kaushik-da (Kaushik Ganguly), Arindam-da (Arindam Sil), young film-makers like Mainak Bhaumik have changed the way Bengali films are made and perceived. A new breed of film-makers and technicians have highlighted the importance of make-up in the scheme of the films as a whole. Stars have begun to appreciate the contribution of technicians who have a huge role to play in accentuating their ‘star presence’.

In the last 4-5 years, I have worked on films like Buno Haansh and Dhananjay which had deceptively simple but demanding make-up requirements. I am especially fond of my work in Aniruddha Roy Chowdhury’s Buno Haansh – which presented Dev with a new look. Arindam Sil’s Dhananjay gave me a lot of satisfaction. Based as it is on a true story, with a court case that went on for years, it offered the opportunity of working on the characters’ looks changing over fourteen years. It was wonderful to work with Anirban and his look in this. As also, with Sudipta Chakraborty (she played Hetal Parekh’s mother whose evidence nails Dhananjay), who in my opinion is the most versatile actor in the industry today.

Of course, I need to mention Vinci Da – it was quite something to have a film evolve from my own personal experiences as a make-up artist. I had created something quite scary for a film which the director eventually decided not to show – he wasn’t sure the audiences would be comfortable. I had put in a lot of work on the make-up and was disappointed. Rudranil Ghosh developed the story from there and then Srijit-da made the film. It was the story of a make-up artist and there was a lot of dramatic potential in the work that I did.

I also enjoyed shooting Indrajit Das Gupta’s Agantuk, where I have given Sohini Sarkar the look of a seventy-year-old woman. Its release got stalled because of the lockdown.

What is the makeup artist’s biggest contribution to the film?

Most people, even in the industry, let alone the general public, do not realize that the make-up department is one of the pillars of a film. Make-up department, costume, lights – the edifice of a film stands on these as much as its stars. It is the make-up that transforms a star into a character as per the demands of the script. In my opinion, when the day’s shoot begins, it is in the make-up room that the actor gets in the mood for the scene he or she is to shoot. That is the make-up artist’s biggest contribution. He helps the actor get into the skin of the character. Another aspect of our contribution that few people understand lies in the way we handle budgets. Bengali films do not have big budgets – so it is always a race against time. I finished Vinci Da in twelve days, Kakababur Protyaborton in thirteen. Because time saved is money saved. To deliver all those special requirements without going for CG, and at the same time keeping it realistic, without compromising on the final look … This holds true for other departments too – art, lights …

How do you see the Bengali industry vis-à-vis other industries?

I can say without hesitation that make-up in the Bengali industry is now of international standards. Just look at the work of Ram Rajak, who won a National Award in Nagarkirtan. We are at par with the Hindi film industry – in fact, given our budgetary constraints I would say we are doing much better. If we had the kind of money that Hindi or Tamil films have, we could have done wonders. We no longer have to get stalwarts from other industries for our requirements. There is enough talent in Bengal delivering work of the highest order. The work that we do despite the odds makes me believe that it’s only a matter of time before we get there and compete against the best internationally.

.jpg)