Shashi Kapoor: Once Upon A Time- Unjinxed

Sharmeelee (1971), Siddhartha (1972), Chor Machaye Shor (1974) were the few films that helped to lift the dark clouds. Soon my cup runneth over, and I was in control of my life all over again. Not that the happy phase lasted too long. In 1972, I was in London, watching Lawrence of Arabia. Suddenly, I get an urgent message on the BBC asking me to rush home immediately. My father was unwell. I took a flight on the same night to Bombay. It was a depressing journey. There were all kinds of thoughts in my mind. I was too upset but at the same time, for my own peace, I tried dozing off That's when I realised that the body has its own defence mechanism and however grave the mental preoccupation, it inevitably finds a way of rejuvenating itself. On landing, I was told that my luggage would be taken care of and I may rush to the hospital. Outside Tata Hospital was a huge crowd. As soon as I entered the gate, the crowd rushed towards me for autographs. It was pathetic! How could anybody be so insensitive to someone whose father was on his deathbed? The entire family had collected by his bedside. My father had been in a coma for almost 30 hours. The only time he opened his eyes, was to ask if I had returned. When I went near his bed and said, "Papaji," he opened his eyes and blinked. It was the quickest movement he had made in the last three days. The doctor told us his time was up thirty hours ago. But he was clinging on, waiting for me... He had met everyone except me and kept asking, "Shashiaaya...? Shashiaaya?" Funny how we don't believe such things when we read them in books. But they do happen. When he hugged me, his embrace was so tight that it almost took my breath away. It wasn't the embrace of a sick man. I sat beside him on his bed, held his hand and talked to him... He talked ...There was no sound, but his lips moved, his eyes expressed things I could not make out, but I understood. He appeared calm. There was no conflict. There was a smile on his face...and as seconds clicked by, his smile turned broader. Exactly like it happens to a 'close-up' in a film and suddenly the shot froze. Suddenly it was all over. Outside, it was 11 a.m. The sun was a beautiful orange in the sky. Exactly the way he would have liked it. He always spoke about the sun. "I am a-Kshatriya," he said. "One morning, I will get up, have a bath, look at the sun and go..." The nurse had given him a sponge bath in the morning. He didn't get to look at the sun. The windows of his room were shut but at least the sun was smiling outside. Welcoming a great soul to heaven. Strangely, my mother, who, all of us expected to be totally broken was the most self-possessed. In fact, she consoled us kids. "He is at peace with himself. And I will soon follow him. Our duties in this world are over," she said. In just a few months time, Chaiji too fell seriously ill. Again, cancer. Even though we had got her uterus removed, the disease had spread all over the body. And God, how she suffered. But not once in all the pain she went through, did she complain. She bore it all in silence, like a tapasvani. When the time was up, she folded her hands, closed her eyes and went quietly. Like my father, her face too was a picture of calmness.

My parents' demise left me with an aching vacuum. I was filled with a sudden loneliness I could not describe. I realised that a human being can feel like a child, only as long as his parents live. His age has got nothing to do with this. A person without parents can never feel like a child again. A man needs his parents. They are his anchor. A woman has her man, she can depend on him. But a man has no one except his parents. As long as they were alive, I visited them whenever I was distressed. Often, I'd stop on my way home, spend an hour or two, have a meal with them. I didn't have to say anything, but when I returned home, I felt tranquil. I must have never told my problems to my father and yet, somehow my father always knew when I was disturbed. When I'd be leaving, he would pat me on the back and say, "it will all be okay."

.jpg/Pics%201%20(2)__600x458.jpg)

There was something so reassuring about the way he said it that instantly something got resolved for me.

I guess that's what being a parent is all about. Today, when I see either of my kids looking disturbed, I don't ask them questions. I try and comfort them exactly the way my father comforted me. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it doesn't.

There came a phase, sometime in the late seventies, when I turned into a work maniac. It was the busiest phase of my career when I was doing five shifts a day. I ran from one studio to another, shooting for sometimes two, sometimes three hours only. I had signed so many films that everyone in the industry said I was going potty. The producers timed their watches on my arrival. The common line used for me was "Shashi ka kaam pehle karo, woh do ghante mein chala jayega." Raj Kapoor who had signed me for Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978) couldn't come to terms with this new star system, "Actor hoya taxi?" Soon, a new name was coined for me. Taxi Kapoor. My meter was on all the time. Physically overworked, I was turning ill-tempered. I was easily irritable and annoyed a lot of people. The press had begun to write about me as the actor of 500 films fame.' It was a tag that never left me. I couldn't give a damn. There was no time to reflect, to think, to analyse

or to introspect. I missed my parents desperately. I missed idling. I longed to spend an evening at home, and have a drink watching the sunset. It was days since I had seen the sunset...days since I had returned home early... Suddenly, these little joys seemed very precious.

Despite so much chaos, I was surprised that there were more producers wanting to sign me. "Mujhe marne ka time nahin," I told them but they persisted. One of whom was Arvind Sen. He had been hounding me for an appointment for days. He insisted that I hear his script, or at least his song. "Give me only five minutes," he pleaded. The song went something like, kya karoon bhai mujhko time nahin, I was amused. The identification was overwhelming and even though I didn't want to agree, I said 'yes' to Arvind Sen. The film was Atithee (1978) and like most of my other films during that phase, this film too bombed at the box-office. Not that it mattered to me. Nothing did, as long as I could fulfil my two dreams, a goal I had marked for myself. One, to resurrect Prithvi Theatre, my father's aborted dream. Two, to open my own production company, `Filmwalas.' I longed to roll big films, good films, meaningful films. Films that would do my banner proud. We decided to start with Shyam Benegal.

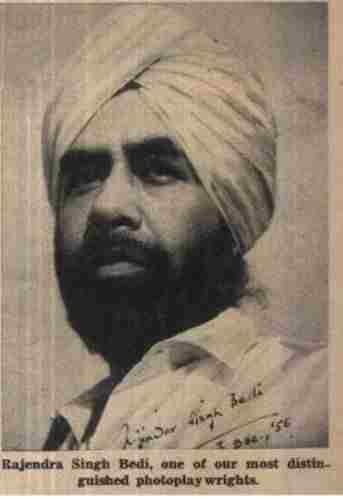

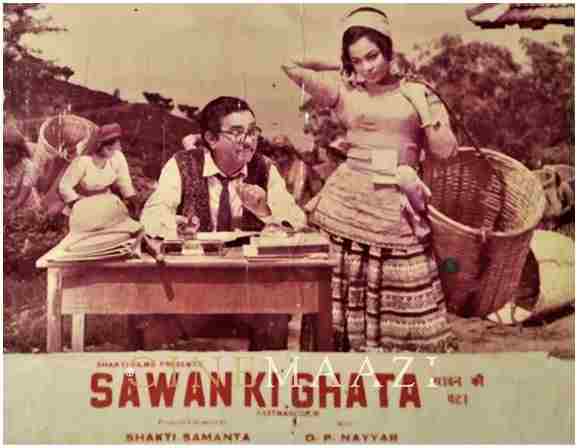

This article was originally published in May 1991 as the first chapter of Junio G magazine's supplementary issue- Shahsi Kapoor: Once Upon A Time. The image used has been taken from the original article and Cinemaazi archive

About the Author

.jpg)